Chapter 7: Britain is Exceptional

How the Myth of British Exceptionalism Brought the UK to Its Knees

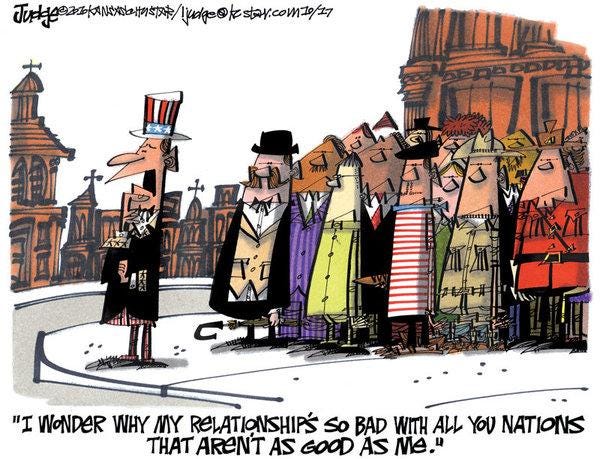

At the core of British politics and culture lies an enduring yet contentious concept: British Exceptionalism. This is not merely a view of the UK as being unique, but often that it is better than other nations. In the words of Tony Blair, “This is the greatest nation on Earth.” Similarly, Boris Johnson declared that “This is the greatest place on Earth, and it is going to be even greater.” This notion, ingrained in the national consciousness, posits that Britain's history, culture, and global role are uniquely distinct and superior. Over the past 40 years, a chorus of British Prime Ministers, regardless of party lines, have echoed this sentiment, each weaving their own thread into the tapestry of exceptionalism through their rhetoric. Whether it’s Tony Blair's emphasis on Britain's 'moral responsibility' in international affairs, and Boris Johnson's nostalgia for Britain's imperial past— British establishment voices collectively reinforce the narrative of a Britain set apart from the rest of the world.

This chapter aims to dissect the construct of British Exceptionalism, laying bare its foundations and exploring how this ideology has been propagated It will explore the diverse rationales employed to justify British Exceptionalism. It will scrutinise the myths versus the realities, dissecting how historical narratives have been selectively used to construct a story of exceptionalism. We will also examine case studies to assess the impact of this ideology on political debate and policy in the UK. By exploring the intersection of education, politics, and media, we aim to unravel how British Exceptionalism has been woven into the very fabric of the nation's identity and how it has contributed to the breaking of Britain.

Through this exploration, we will shed light on the complexities and nuances of British Exceptionalism, challenging the reader to rethink conventional narratives and consider the implications of this ideology on both national and global scales.

National Exceptionalism and its Varied Forms

National exceptionalism, a concept deeply interwoven into the fabric of various nations' identities, posits that certain countries possess unique qualities that set them apart and often above others. Rooted in distinct historical events and cultural narratives, this idea shapes the national psyche and foreign policy of countries like Russia, America, and France, each with its own version of exceptionalism.

In the United States, American exceptionalism springs from the nation's founding principles and the American Revolution. The U.S. is portrayed as a unique bastion of freedom, democracy, and opportunity—a "city upon a hill" with a moral responsibility to lead by example. This exceptionalism is embodied in the country's commitment to liberty and democracy, individualism, and the American Dream, suggesting that anyone can achieve success through hard work.

Russian exceptionalism, meanwhile, is steeped in the nation's long history, characterized by its vast geography, Orthodox Christianity, and a strong central state. This exceptionalism often emphasizes Russia's role as a defender of traditional values against Western liberalism and its historical destiny as a global power, drawing from a sense of historical continuity from the Tsarist empire through the Soviet era.

French exceptionalism centres around its cultural richness, intellectual tradition, and the revolutionary values of liberté, égalité, fraternité. Stemming from the French Revolution, this narrative highlights France's role in shaping modern democratic ideals and its influence in art, philosophy, and culture, emphasizing the state's importance in preserving cultural identity and social solidarity.

Despite these varied manifestations, common threads run through these narratives of exceptionalism. All are deeply rooted in significant historical events—the American Revolution, the establishment and expansion of the Russian Empire, and the French Revolution. Each country perceives itself as having a global mission, whether it's spreading democracy, protecting traditional values, or promoting universal rights, and sees itself as a cultural beacon, influencing global arts, literature, and thought.

However, there are notable differences. While American exceptionalism focuses on democracy and individual freedom, Russian exceptionalism is more about state power and traditionalism, and French exceptionalism centres on intellectual leadership and secularism. The U.S. often evokes a sense of manifest destiny and pioneering spirit, whereas Russian exceptionalism emphasizes historical continuity and endurance. French exceptionalism positions its values as universally applicable, contrasting with the more distinct paths and models of American and Russian exceptionalism.

These narratives play a crucial role in shaping each nation's self-identity and foreign policy, reflecting their diverse paths and roles in the global arena. Understanding these nuances is key to comprehending international relations and the perspectives that drive these nations. Each country's sense of exceptionalism, deeply rooted in key historical events, has become an integral part of its national psyche, often evoked in political and cultural discourse to reinforce a sense of uniqueness and destiny.

The Conservative Saga of British Exceptionalism

British Exceptionalism, akin to other forms of national exceptionalism, possesses its own distinctive qualities. Advocates of British Exceptionalism often present arguments similar to the following, conveyed here with a hint of irony to highlight the often exaggerated and romanticised narrative of this concept:

In the annals of history, the narrative of Great British Freedom begins with the Magna Carta in 1215, a monumental testament to the nation's early commitment to justice and the rule of law. This historic document laid the groundwork for modern democracy, embodying the principles of liberty and fairness. Critics who dismiss the Magna Carta as a mere political manoeuvre overlook its broader impact on the course of democratic evolution, which was deeply rooted in Britain’s moral and cultural ethos.

The journey towards liberty was further advanced through the English Reformation. This period marked Britain’s bold stride towards religious freedom and tolerance, challenging the authoritarian control of the Roman Catholic Church. While detractors might attribute this to political motives under Henry VIII, and highlight the subsequent violent oppression of Roman Catholics, such criticisms overlook the profound shift towards enlightenment, individual liberty, and religious inquiry that it heralded, laying the foundation for modern British values.

The expansion of the British Empire was a colossal endeavour of moral purpose. Far from being an exercise in mere dominion, the Empire symbolised Britain's commitment to bringing progress, civilisation, and enlightenment to less developed parts of the world. This period witnessed the introduction of railways, telecommunication systems, and educational reforms, spearheading global development and free trade. Although some critics depict the Empire as a vehicle for exploitation and dominance, and there were occasional moral transgressions and deviations from the Empire’s moral purpose, these transgressions are overshadowed by the undeniable advancements the Empire brought in governance, infrastructure, technology, and societal structures across the globe.

The zenith of British exceptionalism is epitomized in its role during World War II. Britain's solitary stand against Nazi Germany wasn't merely a battle for survival; it was a moral crusade, a testament to the nation's unyielding dedication to the greater good of civilisation. This era, particularly the Battle of Britain, showcased Britain's resilience and military strength, reinforcing its commitment to national independence and global liberty. Critics downplaying Britain's role as more circumstantial than deliberate neglect the undeniable spirit and courage that Britain demonstrated as Europe's last bastion of hope against tyranny.

In summation, from the foundational Magna Carta to the transformative English Reformation, through the morally driven mission of the British Empire, and culminating in the heroic stand during World War II, Britain's historical journey is a saga of righteousness. Despite detractors' views, the nation's distinct role in shaping the modern world, underscored by its commitment to liberty, justice, and progress, continues to be a source of national pride and global admiration.

Deconstructing the Conservative Myth of British Exceptionalism

While the traditional narrative of Great British Freedom, beginning with the Magna Carta in 1215 and extending through the British Empire to World War II, portrays a saga of progressively increasing liberty, democracy, and moral enlightenment, a critical examination of this narrative unveils a more complex and often contradictory reality. It is also noteworthy that all of the events frequently said to define Britain’s special nature are primarily English events. British exceptionalism is, in reality, Anglo-British exceptionalism.

The Magna Carta of 1215 is often celebrated as a foundational moment in the development of democratic governance. Nonetheless, its actual historical context and impact paint a different picture. The document was primarily a practical response to a political crisis, aimed at appeasing rebellious barons, not a deliberate step towards modern democracy. Its provisions largely catered to the interests of the nobility rather than the common people and had little to do with establishing principles of liberty and fairness for the broader population. Furthermore, its effects were not long-lasting or widely felt at the time, as it was nullified within a few months.

The English Reformation, while a significant historical event, was more a political manoeuvre by Henry VIII to consolidate power and wealth than a genuine movement towards religious freedom and enlightenment. The dissolution of monasteries and the establishment of the Church of England were primarily driven by the King's desire for an annulment and control over church revenues. This period also saw increased persecution of those who opposed the new religious order, including the execution of Roman Catholics and other dissenters. Contrary to being a step towards religious freedom, the Reformation heralded a new form of religious authoritarianism under the monarchy.

The imposition of Protestantism in Ireland during the English Reformation and subsequent years had profound and devastating impacts on the predominantly Catholic population of Ireland. The enforcement of Protestant supremacy effectively criminalised the majority of the population in Ireland. Large-scale confiscations of land from Catholic nobility and commoners alike redistributed wealth and power to Protestant settlers, particularly in the wake of rebellions. The consequence was that the majority of people in Ireland were barred from holding public office, faced restrictions on their worship, had few property rights, and suffered significant discrimination. The celebration of this period of the United Kingdom’s history as enlightened is puzzling.

The expansion of the British Empire, glorified as a mission to spread civilisation, technology, and free trade, was largely an endeavour of economic exploitation, cultural domination, and territorial expansion at the expense of indigenous populations. European powers sought wealth and feared the consequences of being left behind by their peers if they failed to acquire lucrative colonies. Although the British introduced certain infrastructural and administrative reforms in their colonies, these were typically designed to better exploit the resources and labour of colonised peoples. The Empire's legacy includes numerous instances of oppression, exploitation, famine, and cultural destruction.

The colonisation of Australia had a catastrophic impact on indigenous communities. It's estimated that the indigenous population, which stood at around 750,000 to 1.25 million before European settlement, dropped significantly due to diseases, dispossession, and direct conflict. While exact numbers are debated, some estimates suggest that the population declined by over 90% in the 150 years following colonisation. Such destruction cannot be ‘balanced’ by the introduction of railways of other technologies given that such technologies could have been shared without bloody conquest. The narrative of a ‘moral purpose’ masks the harsher realities of colonial rule and the suffering inflicted on millions.

The British Empire, in its pursuit of trade interests, notably in tea, silk, and porcelain, resorted to selling opium in China. This led to widespread addiction, social disruption, and the eventual Opium Wars (1839-1860). The wars, fought to protect British commercial interests, led to significant Chinese casualties and the cession of Hong Kong to Britain.

A more recently popular pro-Empire narrative highlights the role of Britain in ending the trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. This tale tends to downplay the significant role of the British Empire in the transatlantic slave trade whereby millions of Africans were forcibly transported to the Americas under horrific conditions. The United Kingdom's relationship with slavery, often perceived as decisively ended with the 1833 Abolition of Slavery Act, was in reality far more complex and protracted. The Act, initially applied only in the West Indies, did not immediately or comprehensively abolish slavery across the British Empire. This gradual implementation meant that slavery persisted in regions like the Gold Coast until 1874 and in southern Nigeria until 1916.

Even where officially abolished, forms of forced servitude continued, as seen in the Gambia, where a 1906 ordinance stipulated that existing slaves were to be freed only upon their masters' death. In Sierra Leone, a 1901 ordinance halted the slave trade but allowed personal use of slaves, reflecting the Empire's reluctance to fully relinquish slave practices. Economic concerns often outweighed moral imperatives, as highlighted by Winston Churchill's 1921 response prioritising Sierra Leone's financial stability over the abolition of slavery.

The early 20th century saw Britain under pressure from the League of Nations to address the ongoing practice of slavery in its colonies. Despite Britain's admission in 1924 of slavery's persistence in territories including Sierra Leone, northern Nigeria, and Gambia, and despite its signing of the League of Nations slavery convention in 1926, meaningful change was slow. The legal status of slavery in Sierra Leone was shockingly acknowledged in a 1927 Supreme Court ruling, which even permitted force in retaking runaway slaves.

It was not until January 1, 1928, nearly a century after the supposed Empire-wide abolition, that slavery was fully abolished in Sierra Leone, a settlement ironically established for freed slaves. This belated abolition, contrasting sharply with the earlier legislative act of 1833, underscores the gradual, reluctant, and economically influenced approach of the British Empire in ending its involvement in slavery, revealing a far more intricate and extended timeline than commonly acknowledged.

Britain's role in World War II, particularly during the Battle of Britain, is rightly remembered for its heroism and resilience. Yet, contemporary discourse sometimes conflates retrospective justifications for the conflict with the historical reality. The commonly held belief that the United Kingdom entered World War II primarily to save the Jews from the Holocaust or to oppose Hitler's tyranny is a misconception. In reality, the UK's motivations for entering the war were driven by a complex mix of geopolitical, strategic, and national security concerns. The British declaration of war in September 1939 was a direct response to Hitler's invasion of Poland, an act that breached the Munich Agreement and posed a direct threat to the European balance of power, which the UK was keen to maintain.

Furthermore, at the time of entering the war, the full extent of the Holocaust was not widely known or understood. The systematic extermination of Jews and other groups by the Nazis only became fully apparent later in the war. British war efforts, while instrumental in eventually liberating concentration camps and ending the Nazi regime, were not initially motivated by a desire to end the Holocaust, which was largely unknown to the broader public and policymakers at the war's outset.

This is not to diminish the moral stance taken by the UK against Nazi atrocities once they were uncovered, but it is important to acknowledge that the primary reasons for the UK's involvement in WWII were rooted in traditional statecraft and strategic considerations rather than a humanitarian intervention to stop the Holocaust or promote democracy and human rights.

In addition, the UK’s stand against the Axis powers was also part of a broader alliance with other nations, including the Soviet Union and the United States, whose contributions were equally crucial. The war effort relied heavily on resources and soldiers from the Empire, often without adequate recognition of their sacrifices. Many other Commonwealth countries have an equal claim to having contributed to defeating Nazism.

In conclusion, despite the elements of progress and enlightenment in British history, the narrative of an unbroken evolution of liberty, justice, and moral superiority is overly simplistic and often misleading. Each of these historical milestones – the Magna Carta, the English Reformation, the British Empire, and World War II – contains a more complex and less flattering truth. The traditional, conservative narrative of British exceptionalism, with its focus on righteousness and global influence, needs to be critically reevaluated in the light of historical evidence and the perspectives of those who were marginalized and oppressed in this process.

A Liberal Narrative of British Exceptionalism

While it's easy to dismantle the traditional, jingoistic, conservative version of British exceptionalism, there's an alternative, more nuanced narrative that socially liberal Brits often champion. This perspective reimagines British Exceptionalism, rooting it not in the Magna Carta or the Reformation but in the early 20th century. It highlights Britain's pivotal role in creating a rules-based international order and setting global human rights standards.

The core of this hypothesis is the UK's instrumental involvement in forming key international organisations. In the aftermath of the devastation wrought by World War I and World War II, Britain was crucial in the establishment of the League of Nations and the United Nations. These organisations, shaped significantly by British diplomatic strategies and vision, laid the foundations for international cooperation and the establishment of human rights norms, setting a new benchmark in global governance.

Moreover, this hypothesis emphasises the UK's significant contribution to drafting seminal human rights documents. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) bear the unmistakable imprints of British legal expertise. British jurists and legal scholars played crucial roles in their formulation, making these documents foundational texts in international human rights law.

Further supporting this hypothesis is the UK's essential role in the development and ratification of major international human rights treaties. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), which expanded upon the rights outlined in the UDHR, were significantly influenced by the UK's legal prowess. The UK's involvement in drafting and ratifying these covenants is presented as evidence of its unwavering commitment to a comprehensive human rights framework.

Additionally, the UK's active participation in conventions like the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) is highlighted as demonstrative of its broader commitment to advancing human rights in specific areas. These conventions, which are crucial in promoting gender equality and children's rights, have benefited immensely from the UK's advocacy and support.

Supporters of this 'liberal' hypothesis further point to the UK's role in establishing the Council of Europe as evidence of its dedication to human rights. The formation of the Council, and the subsequent emergence of the ECHR from it, heavily influenced by British legal principles, have been pivotal in shaping human rights practices across Europe.

Thus, this alternative hypothesis of British Exceptionalism, centred around human rights, presents a complex and layered narrative. It suggests that the UK's legacy, encompassing foundational roles in international bodies, influence over pivotal human rights documents, and advocacy for democratic transitions post-colonisation, reflects a unique, deep, and sustained commitment to global human rights issues.

Debunking the Liberal Hypothesis of British Exceptionalism: Colonial Disengagement in the 20th Century

In stark contrast to the polished, high-minded, liberal narrative of British Exceptionalism, which lauds the UK's role in crafting international human rights norms, lies a much less noble reality. The UK's conduct in the 20th century, especially in its former colonies, reveals a tale of brutal contradictions, frequently violating the very international human rights laws it helped to craft. Post-World War II, as the world moved towards decolonisation, Britain’s retreat from empire was anything but the benevolent, orderly withdrawal often depicted. Instead, it was characterised by violent uprisings and long-standing resistance movements, exposing the myth of a benevolent Britain gracefully granting independence.

Take, for instance, the Mau Mau Uprising in Kenya during the 1950s. Here, the British response to the rebellion against oppressive colonial policies, which included apartheid and widespread land confiscations that devastated the Kikuyu people, was nothing short of barbaric. Britain’s reaction involved setting up concentration camps where thousands were detained without trial, subjected to torture, and, in some cases, executed. Collective punishment was the primary strategy employed by British politicians and generals in their suppression of the rebellion. These actions starkly contradicted the human rights principles Britain championed on the global stage.

In Kenya, the UK's actions were driven by naked economic and strategic motives. Kenya's agricultural potential, especially in coffee and tea production, became a goldmine for British exports. The British settlers established large-scale farms, often through the ruthless expropriation of land from the native population, thus cementing Kenya's value to the British Empire. Strategically, Kenya was indispensable for Britain's control over its African territories, serving as a crucial hub for military and administrative operations. These imperial interests were cynically deemed sufficient justification for Britain’s blatant abandonment of its prior humanitarian commitments.

When allegations of human rights abuses in Kenya began to surface in the UK press and parliament, Winston Churchill’s response was to introduce an amnesty for British soldiers and their allies. This blanket protection shielded those involved in the counterinsurgency efforts from prosecution or investigation for human rights abuses or war crimes. It was a calculated move to protect British personnel from legal and political consequences, maintaining morale and discipline within the ranks at the expense of justice and human rights.

Simultaneously, the Malayan Emergency (1948-1960) unfolded with similarly oppressive tactics. The rebellion in Malaya was driven by a mix of political and economic factors, with many Malayans yearning for independence and self-governance. This desire was fuelled by global decolonisation trends, a desire for socialism and dissatisfaction with British policies that created economic disparities and favoured certain ethnic groups.

Britain's interest in maintaining control over Malaya was primarily economic, given its status as one of the world's largest producers of tin and rubber. Malaya's strategic location in Southeast Asia also made it vital for controlling trade routes and regional influence. To suppress the Malayan Emergency, Britain employed brutal strategies, including the forced relocation of hundreds of thousands of people into new villages under the Briggs Plan, disrupting lives and communities. British forces also engaged in ground operations and aerial bombings, leading to accusations of severe human rights abuses.

British forces in Malaya used extreme and controversial tactics, such as performative mutilations intended to intimidate the local population, which starkly contravened ethical standards and rules of war. The Batang Kali Massacre, where the Scots Guards killed 24 unarmed villagers, remains a dark episode. Despite its gravity, no British soldiers were prosecuted, and subsequent justice efforts were met with limited response from the British government.

Turning to Oman, British involvement since the 1950s further illustrates actions driven predominantly by geopolitical interests rather than democratic values. The UK's special relationship with Oman has led to the establishment of significant military and intelligence infrastructure, including spy bases intercepting vast quantities of communications, highlighting Oman’s strategic importance, particularly near crucial oil shipping routes. Moreover, the establishment of a large British military base at the Duqm port complex underscores its strategic significance for projecting military power in the region.

British oil interests in Oman, especially involving British Petroleum (BP), have been deeply intertwined with the region's geopolitical and economic narratives. The company’s involvement in Oman dates back to the early 1920s, marking the beginning of significant British interest in Middle Eastern oil. Over the decades, BP and other British companies have played pivotal roles in exploring and developing Oman's oil resources.

In the late 1950s, Britain intervened in a conflict in Oman to suppress an uprising against slave-owning Sultan Said bin Taimur's oppressive regime, characterised by a lack of basic freedoms, economic stagnation, and political suppression. Despite recognising the miserable conditions under the Sultan's regime, Britain supported the Sultan, employing the Royal Air Force to bomb rebels and attack civilian infrastructure. This intervention was driven by strategic interests rather than a desire to promote human rights or democracy.

The discovery of oil in commercial quantities in Oman during the 1960s further solidified its strategic importance to Britain, coinciding with a broader strategy of maintaining influence in the Persian Gulf. Support for Sultan Qaboos' coup in 1970 was partly driven by these oil interests, ensuring a stable and favourable regime for safeguarding British oil concessions and investments. Over subsequent decades, British involvement in Oman's oil sector expanded, cementing a lasting partnership between the two nations in energy.

From the 1980s onward, the Britain-Oman relationship has continued to reflect strategic, military, and economic interests. Oman's strategic location at the mouth of the Persian Gulf remains crucial for global oil supplies. Ongoing military cooperation, including training, arms, and advisory support, enabled Britain's policy of maintaining a security presence in the Gulf region.

The economic aspect of the relationship, particularly in the oil sector, continues to be significant, with British companies expanding operations in Oman. However, Oman's political landscape under Sultan Qaboos’s successor, Sultan Haitham bin Tariq, remains largely authoritarian, characterised by limited political freedom, restrictions on free speech, and a lack of robust democratic institutions. Efforts at modernisation and economic diversification have been made, but the political system remains tightly controlled, with little tolerance for dissent. In 2020, Oman introduced a new penal code with harsh penalties against free speech, jailing those who challenge the Sultan's rights, disgrace his person, or undermine the state's stature. These regulations highlight ongoing human rights restrictions and the UK's indifference to the Sultan's subjects' suffering.

Despite these issues, the special relationship between Britain and Oman persists. The UK views Oman as a key ally in a strategically important region, leading to a relationship where economic and strategic interests often overshadow concerns about human rights and democratic values. The continued military, intelligence, and economic ties reflect a long-standing pattern of British foreign policy in the Middle East, prioritising geopolitical interests and stability over democratic governance and human rights promotion.

In summary, examining Britain's actions in Kenya, Malaya, and Oman across the 20th and 21st centuries reveals a consistent pattern of prioritising economic and strategic interests over the democratic principles and human rights standards it helped to establish internationally. Similar accusations of war crimes and human rights violations during the Aden and Cyprus Emergencies further illustrate this. The stark contrast between Britain's global advocacy for human rights and its colonial and post-colonial policies challenges the ‘liberal’ narrative of British Exceptionalism and demands a critical re-evaluation of the UK’s historical legacy in international human rights.

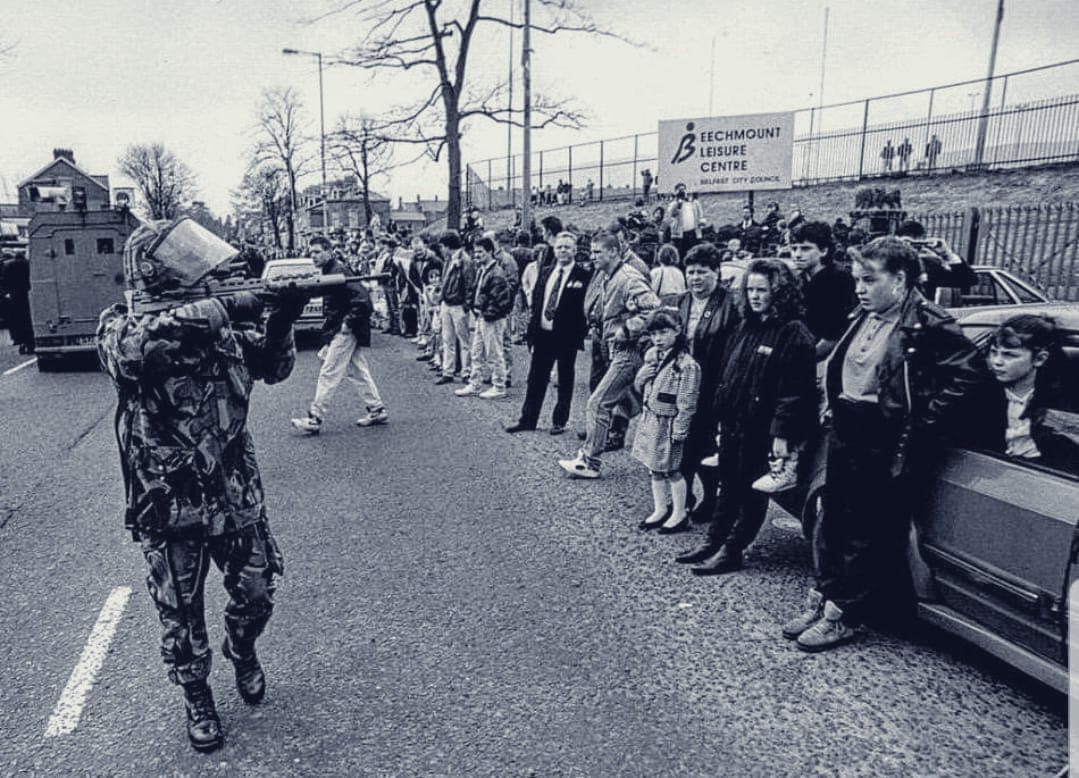

Debunking the Liberal Hypothesis of British Exceptionalism: Northern Ireland’s Illiberal Democracy

The post-WWII portrayal of Britain as a stalwart defender of a rules-based international order and human rights is sharply contradicted by its atrocities in Kenya, Malaysia, and Oman. Proponents of this myth might argue, “Yes, our colonial exploits were regrettable, but domestically, we’ve been a paragon of progress.” They might cite the development of a liberal democracy free from rebellion, the establishment of the welfare state, and incremental advances in the human rights of ethnic and religious minorities, women, and the LGBTQ+ community.

However, this argument falls apart under scrutiny, particularly when examining the United Kingdom's record in Northern Ireland. Here, we find a persistent legacy of systemic oppression and human rights violations, challenging any notion of internal moral superiority.

The partition of Ireland in 1922 marked the beginning of a troubled era for Northern Ireland, characterised by deep-rooted sectarian conflict. The Protestant Unionist majority, seizing control of the local government, systematically reshaped the political and social landscape to entrench divisions and foster widespread discrimination against the Catholic Nationalist minority.

This transformation was primarily driven by significant changes to the voting system. To maintain their political hegemony, Unionist politicians, with support from Westminster, manipulated electoral processes through gerrymandering and the introduction of property qualifications and the business vote. These tactics effectively ensured Unionist control over local councils, even in areas with Nationalist majorities.

The Unionist-dominated local councils' housing allocations had profound implications for voting rights. The "ratepayer franchise" system tied the right to vote in local elections to property ownership or tenancy. Thus, the allocation of a house by the council often equated to securing voting rights. This policy enabled the Unionists to expand their voter base by favouring their community in public housing allocations, simultaneously disenfranchising many Catholics by denying them access to public housing and, consequently, voting rights. This discriminatory practice deepened the socio-economic divide and perpetuated the political marginalisation of the Catholic community.

Employment, particularly in the public sector, was another arena where this systemic bias manifested. Public sector jobs, largely controlled by Unionist-led councils, were more readily awarded to Protestants. Employment security facilitated property ownership or private tenancy, qualifying individuals for the ratepayer franchise and further embedding one's role in civic life. For Catholics, facing discrimination in public sector employment meant not only economic marginalisation but also diminished access to voting rights.

The Orange Order, a Protestant fraternal organisation, significantly influenced this socio-political landscape, especially in private sector employment. With its commitment to Protestant ascendancy and Unionist power, the Order exerted substantial influence in various sectors, including the job market. Membership in the Order often became an unspoken prerequisite for securing certain jobs, particularly in areas or industries like shipbuilding with strong Order ties. This resulted in discriminatory hiring practices that systematically disadvantaged the Catholic community, ensuring that Protestants held key positions in the workforce and thus reinforcing the socio-economic and political dominance of the Unionist community.

Policing in Northern Ireland was steeped in sectarianism and political bias. The early 20th century saw pivotal roles played by the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) and the B-Specials amid political turmoil and sectarian strife. The RIC, increasingly enforcing British rule against the IRA, became synonymous with British oppression. The formation of the B-Specials in 1920, primarily comprising Protestant volunteers, further intensified sectarian tensions due to their anti-Catholic bias.

Following Ireland's partition, the RIC was succeeded by the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), predominantly Protestant and perceived by Catholics as an extension of British and Unionist policies. The RUC and B-Specials, through their actions, deepened communal divides and sowed seeds of mistrust that eventually ignited The Troubles. Their militarised approach starkly contrasted with British police forces, underlining their unique role in a divided society.

The cumulative effect of these discriminatory policies in voting, housing, policing, and employment created a volatile environment, setting the stage for the civil unrest that would escalate into The Troubles. This conflict saw the British government employing counter-insurgency tactics akin to those used during the Mau Mau Uprising in Kenya and the Malayan Emergency. Tactics like internment without trial, initiated in August 1971, were reminiscent of British measures in colonial conflicts. In Northern Ireland, internment almost entirely targeted Catholic and Nationalist communities, exacerbating state-sponsored discrimination perceptions.

Echoing colonial-era conflicts, the British Army's handling of civilians during The Troubles resulted in the deaths of 194 civilians between 1968 and 1993, predominantly Catholics and Nationalists. Contrary to British media narratives, a 2012 study revealed that only 12% of civilians killed by British Security Services were inadvertently caught in crossfire. The pattern of violence against Catholic and Nationalist civilians often escalated following Republican paramilitary attacks on security forces, suggesting a retaliatory nature akin to colonial-era and War of Independence era tactics.

Censorship and civil rights restrictions were also key elements of the British strategy during The Troubles. Measures to control information flow and restrict public gatherings paralleled efforts to suppress dissent in Kenya and Malaya. In Northern Ireland, these took the form of broadcasting bans, press censorship, and restrictions on demonstrations, aiming to limit the IRA's communication capabilities. However, these infringements on civil liberties fuelled discontent and mistrust towards the British government.

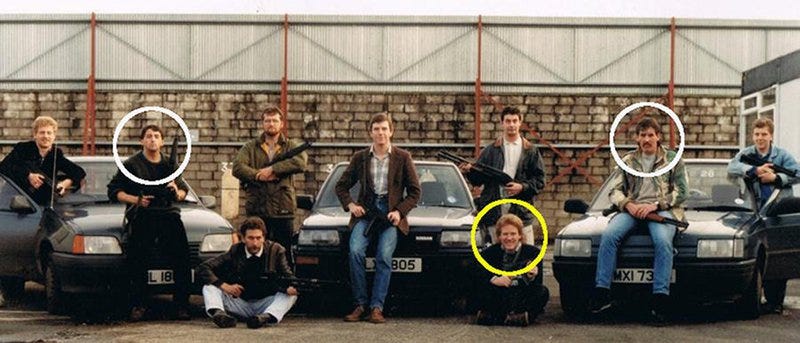

Furthermore, collusion between British security forces and pro-British paramilitaries in Northern Ireland mirrored colonial practices. Covert cooperation between security forces and Loyalist paramilitaries often targeted Nationalist communities, aggravating the sectarian divide and eroding any pretence of impartiality. The Military Reaction Force (MRF) was a covert British Army intelligence unit consisting of members of the British Army in plain clothes operating as a ‘pseudo-gang’ involved not only in infiltration and intelligence-gathering but direct attacks and assassinations; some of an avowedly sectarian nature. As one former member revealed to a BBC Panorama documentary; ‘we were not there to act like an army unit. We were there to act like a terror group’. There are allegations such units worked in tandem with loyalist paramilitaries in some of the most lethal events of the period; such as the McGurk’s bar bombing in 1971 and the Dublin-Monaghan bombings of 1974.

The Military Reaction Force was eventually replaced by the Force Research Unit (FRU). One of the most famous people associated with the FRU was Brian Nelson. After serving in the British Army's Blackwatch Regiment and being discharged on grounds of mental instability, Nelson joined the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) upon returning to Belfast. His violent activities, including abducting and torturing a Catholic man in 1973, potentially marked the beginning of his connection with security forces. In 1984, after avoiding contact with the UDA for a while post-release from prison, Nelson reached out to offer his services to the Intelligence Section in Lisburn Garrison and was subsequently met by personnel from the FRU. Despite evidence of his mental instability and sectarian brutality, the FRU tasked Nelson to rejoin the UDA, where he was soon appointed as the Intelligence Officer for West Belfast.

During his time with the UDA, Nelson played a dual role as an FRU agent and a UDA operative. In consultation with his handlers, Nelson passed on information from security services to the UDA allowing for the identification, targeting, and assassination of individuals associated with nationalist or republican groups, as well as others who were not involved in the conflict but were targeted due to their perceived political or religious affiliations. Nelson’s role exemplified by his involvement in a significant arms procurement.

In June 1987, Nelson travelled to South Africa, where, with the assistance of another British agent, Charles Simpson of MI5, he successfully procured a shipment of illegal arms for loyalist paramilitaries. The deal included procuring weapons and ammunition worth £100,000, comprising assault rifles, pistols, and explosives. To date, these weapons have been linked to over 100 killings.

Formal and informal collusion between loyalist paramilitaries and locally-recruited state forces, particularly the Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR), was rampant. Most notoriously, between 1971 and 1978 a group of loyalists known as the ‘Glennane Gang’ killed some 120 people in counties Tyrone and Armagh. Many of those directly involved were members of the RUC and the UDR and there is substantial evidence they received help and support from senior intelligence officials in what amounted to a campaign of total war.

During the early stages of The Troubles, the British Army was largely self-regulated. This autonomy resulted in opaque investigations and a notable absence of legal actions against human rights abuses perpetrated by security forces. The rationale behind this lack of accountability was to preserve military morale and uphold national security. However, this approach only served to deepen the sense of distrust and bitterness within the Nationalist and Catholic communities. This manifestation of state-endorsed prejudice and injustice echoed historical colonial practices, wherein British troops and their allies seldom faced repercussions for their misconduct. The aftermath of these policies saw years of obfuscation, with families of the victims tirelessly advocating for the investigation and prosecution of British soldiers implicated in the deaths of their loved ones. In response to these prolonged efforts, the British government, in 2023, enacted an amnesty. This legislation effectively prohibited any future inquiries or legal proceedings related to the killings during The Troubles as was opposed by an overwhelming majority in Northern Ireland.

The tactics employed by the British government during The Troubles in Northern Ireland were not unique but reflected a continuity with colonial-era strategies. Internment, civilian attacks, collusion with paramilitaries, censorship, and civil rights infringements comprised a well-established British counter-insurgency repertoire. Thus, just as narratives of British Exceptionalism based on lawfulness and morality are undermined by colonial human rights violations and support for illiberal regimes, the UK's domestic record, particularly its record in Northern Ireland, reveals a similar disregard for human rights and democratic principles.

A Cascading Sense of Superiority: The Role of Elite Education in Perpetuating British Exceptionalism

Our critique of British exceptionalism is not intended to portray the United Kingdom as inherently evil or morally inferior. When it comes to human rights, the UK's record is comparable to that of other former colonial western democracies. The point is that the UK is simply another ‘normal’ country, with its version of exceptionalism being unfounded and without merit, much like the exceptionalism narratives in the United States, France, and Russia. However, while the UK may be just another ‘normal’ former coloniser with a history of exceptionalism, it does possess unique features.

A significant contributor to the pervasiveness of British Exceptionalism in contemporary socio-political discourse is the influence of the British public school system, particularly its elite boarding schools. These institutions have been instrumental in fostering what psychoanalyst Joy Schaverien terms the "Boarding School Syndrome." This syndrome, characterised by emotional detachment, cynicism, and a pronounced sense of exceptionalism, is evident not only in the attitudes and behaviours of notable public figures like Rishi Sunak but also in the institutional cultures and national attitudes.

As discussed in Chapter 2, alumni of these elite institutions have historically dominated British political and media establishments. Their prevalence has facilitated the transmission of British Exceptionalism into broader political and media discourse, embedding these ideas into the national consciousness and shaping public perception

Boris Johnson, an Eton alumnus, epitomises this personality type. A letter from his classics master, Martin Hammond, in 1982, expressed concerns about Johnson's perceived sense of "effortless superiority" and detachment from the "network of obligation that binds everyone else." As Prime Minister, Johnson's attitudes and policies can be seen as extensions of these formative traits, although it is important to recognise that he represents one end of a spectrum of influences that such an educational background can have.

The curriculum and extracurricular activities in these elite schools historically complemented Britain's imperial ambitions, cultivating a mindset conducive to sustaining the British Empire. This education instilled a deep-seated belief in British superiority and a sense of ordained duty towards global leadership and governance, significantly influencing the development of a cultural narrative equating British identity with exceptionalism and global pre-eminence.

The psychological patterns ingrained through such education have profound implications for personal and professional conduct. This mindset manifests in a resistance to acknowledging personal failures or underperformances, often leading to blame deflection or rationalisation. At the national level, this manifests as a reluctance to acknowledge the UK's failings or underperformance on the global stage.

To navigate its place in an increasingly interconnected and interdependent global community, the UK must recognise and address the deeply ingrained mindset of British Exceptionalism fostered by its elite educational system. As the UK charts its course in the post-Brexit era, critically reflecting on its exceptionalist beliefs and adapting to a rapidly changing world will be crucial for its success and relevance on the international stage.

Introduction to Case Studies on British Exceptionalism

The concept of British Exceptionalism, particularly its specific manifestation as Anglo-British Exceptionalism, is a multifaceted notion that has significantly shaped the UK's political and social landscape. To understand the real-world implications of this ideology, it is essential to examine it through the lens of contemporary events. The following section presents three case studies, each illustrating the negative impacts of British Exceptionalism in different contexts: Brexit, the UK's response to the Covid-19 pandemic, and the UK government's response to the Scottish government's attempt to introduce Self-ID for Gender Recognition Certificates.

Each case example aims to provide a nuanced understanding of how the ideology of British Exceptionalism, and its specific expression in Anglo-British terms, can affect policy-making, societal attitudes, and governance. By analysing these instances, we can gain insights into the complexities and challenges posed by this deeply ingrained belief system within the context of contemporary British society.

Case Study 1: Brexit and Britain's Relationship with the EU

The United Kingdom's protracted engagement with the European Union offers a stark narrative of British exceptionalism—a belief in inherent supremacy, entitlement to preferential treatment, and an insistence that the UK should not be bound by the same rules as other nations.

When the UK joined the European Economic Community in 1973, it wasn't out of a passionate desire for European unity but rather a somewhat cold, calculated decision based on economic benefit. This mercenary approach set the stage for the UK’s approach to European affairs. In the years to come, the UK carved out bespoke and highly favourable arrangements with the larger EU framework. This was marked by features such as the British rebate, the retention of the Pound Sterling and opting out of the Schengen area. However, domestically these concessions were not interpreted as showcasing EU flexibility, but as evidence of British exceptionalism and its natural right to superior treatment. No matter the concessions granted to the UK, British politicians often framed them as triumphs over a nefarious EU scheme. This narrative, fuelled by media and political rhetoric, painted the UK not as part of a greater whole but as an entity distinct from, and frequently at odds with, the EU. The story was clear: the UK was perpetually on the defence, protecting its sovereignty from the encroaching influence of the continent.

David Cameron's attempts in 2015 to renegotiate the UK's EU membership terms highlighted this dynamic. His goal was to curb free movement, despite evidence that EU immigration economically benefited the UK. Cameron’s stance directly challenged the EU's core principle of the indivisibility of the four freedoms: movement of goods, capital, services, and people. His strategy revealed a profound misunderstanding of the EU’s priorities, particularly the inviolability of the Single Market.

Cameron’s gamble, rooted in an inflated sense of the UK's negotiating position, failed spectacularly. His approach laid bare the EU’s commitment to its foundational principles over the UK's membership. Domestically, some believed Cameron's failure was due to insufficient resolve, thinking he hadn't threatened to leave convincingly enough. This perspective highlighted the disconnect between British expectations and reality. His miscalculations not only showcased the UK's exaggerated sense of influence but also set the stage for the Brexit referendum, where these flawed perceptions culminated dramatically.

Both Brexit campaigns appealed to different conceptions of British exceptionalism. The Remain side, led by Cameron, argued that EU membership amplified British influence. This liberal model of exceptionalism called on Britain’s duty to lead Europe, encapsulated in Cameron's assertion, “Brits don't quit We get involved, we take a lead, we make a difference, we get things done.” Conversely, the Leave faction, led by Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage, championed a Conservative model, emphasising the UK's historical prestige and democratic heritage. Johnson’s claim, “We will take back control of roughly £350 million per week,” and Farage's call, “We want our country back,” resonated with a desire to reclaim perceived lost sovereignty.

Despite experts clarifying that UK sovereignty remained intact within the EU, such reassurances fell on deaf ears. Michael Gove’s dismissal of expert analysis—“People in this country have had enough of experts”—epitomised the Leave campaign’s preference for nationalist sentiment over fact-based arguments. This was further amplified by Eurosceptic media, exemplified by The Sun’s “BeLeave in Britain” headline. The Leave campaign’s mantra, ‘They need us more than we need them,’ reflected a delusion of British supremacy, assuming the UK’s singular superiority over 27 other European nations.

Thus, Brexit was framed as a reclamation of British sovereignty, an effort to restore the nation's perceived historical global prominence. The EU, often depicted as a hindrance to British advancement, stood in stark contrast to the reality where EU membership had significantly bolstered Britain's influence and status. This skewed portrayal of the EU's role, intertwined with a deep-seated belief in British exceptionalism, helped to secure a vote in favour of leaving the EU.

The subsequent Brexit negotiations offered more evidence of a profound misalignment in expectations between the UK and the EU, underscoring the intricate dynamics at play and the persistent theme of British exceptionalism. Early on during negotiations, Brexit Secretary David Davis was criticised for employing a “divide and rule” strategy, leveraging the UK's military prowess during a tour of the Baltic states to try and influence individual EU members. This approach, however, clashed directly with EU rules prohibiting individual member state deals and found little support.

EU leaders, steadfast in their unity, rallied behind the European Commission’s negotiation team. This solidarity starkly highlighted the UK’s misjudgment of EU cohesion and its own influence. British negotiators seemed to cling to the belief that they could conduct exit negotiations as they had internal EU dealings—through alliances and mutual interests. They appeared blind to the reality that EU member states would no longer accord the UK the same preferential treatment once it had left the union.

As negotiations, progressed, the UK attempted to use its financial obligations, the Northern Ireland dilemma, and the status of EU citizens as bargaining chips. David Davis criticised the EU’s phased approach as “wholly illogical,” but the EU's stance was unyielding, especially on principles concerning Northern Ireland’s peace and the UK’s financial commitments. From the EU’s point of view, treating international obligations related to these matters as bargaining chips was wholly unacceptable. It insisted that future trading arrangements with the UK would only be negotiated once it was satisfied that the UK would meet its existing obligations.

The most contentious element of the Brexit negotiations was undoubtedly the Northern Ireland backstop. This mechanism within the Withdrawal Agreement aimed to safeguard the Good Friday Agreement by preventing a visible land border on the island of Ireland post-Brexit. For many in the EU, the backstop was seen as a generous concession to the UK. Yet, within the UK, it was often misrepresented as a cunning European ploy to ensnare the UK in a customs union indefinitely. This misperception led to the repeated rejection of the deal in Parliament, highlighting the deep divisions and lack of consensus on a Brexit strategy.

Brexit supporters, including prominent figures like Jacob Rees-Mogg and Andrew Bridgen, displayed a striking detachment from reality. Some proposed extreme solutions, such as suggesting that Ireland might leave the EU to avoid a hard border. The absurdity reached new heights when BBC presenter John Humphrys asked Irish Foreign Minister Simon Coveney if Ireland would consider rejoining the UK to resolve the issue. This line of questioning revealed a profound misconception among certain British establishment figures, who seemed to believe that Irish leaders would be willing to sacrifice their actual sovereignty to assuage Britain's misguided sense of lost sovereignty. The fantastical thinking extended to advocating for non-existent technological solutions as alternatives to the backstop. Despite no country on Earth having successfully developed such technology, Brexiters remained undeterred, convinced that Britain could achieve what others had not.

Following the Leave campaign’s victory, Boris Johnson famously declared, "Our policy is having our cake and eating it.” This mindset, deeply embedded in the Brexit negotiations, particularly around the backstop, showcased a belief that global dynamics would adjust to accommodate the UK's departure from the EU. Theresa May’s failure to achieve this impossible feat led to her resignation and the ascendancy of Johnson, the arch-proponent of 'cakeism', as Prime Minister.

In October 2019, an amended deal replaced the backstop with a new arrangement on Northern Ireland. This ‘frontstop’ marked a significant departure from Johnson's earlier promises that there would be no differences between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK post-Brexit. Under this protocol, Northern Ireland remained aligned with certain EU rules, particularly those concerning goods, to prevent a hard border on the island of Ireland. Consequently, while the rest of the UK exited the EU’s Single Market and Customs Union, Northern Ireland continued to follow EU regulations on product standards and customs processes. This created a de facto customs border in the Irish Sea, a compromise that stirred considerable controversy and faced resistance in Parliament.

Despite these challenges, Johnson managed to secure a parliamentary majority for his deal, leading to the UK's formal exit from the EU. However, the subsequent introduction of the UK Internal Market Bill in September 2020, less than a year after the Withdrawal Agreement's ratification, signaled a rapid shift in the UK government's approach. The bill aimed to unilaterally override parts of the Northern Ireland Protocol, with Northern Ireland Secretary Brandon Lewis acknowledging it broke international law in a "specific and limited way." This move sparked significant controversy, suggesting the UK government was willing to disregard international agreements when politically convenient. This episode, yet again, demonstrates the persistence of a belief in British exceptionalism. Even as it threatened to violate international law, the UK continued to criticise other nations, like Russia, for breaching international treaties.

The Brexit episode is a compelling case study of British exceptionalism in action. From its early days in the EU to the dramatic unfolding of Brexit and beyond, the UK consistently exhibited a belief in its own superiority and entitlement to special treatment. Strategies rooted in this belief repeatedly faltered during the Brexit period, yet support for policies based on 'cakeist' assumptions persisted unabated. The Internal Market Bill, in particular, underscored the extent to which the UK was prepared to challenge international norms to uphold this exceptionalist stance.

Case Study 2: The Covid-19 Pandemic as a Competition

The Covid-19 pandemic has been a significant global challenge, with each country facing its own unique set of circumstances. The United Kingdom's response to this crisis has been characterised by a notable sense of exceptionalism, often ignoring the expertise and experience of other countries. This approach has greatly influenced how the pandemic was managed in the UK, affecting both the health and well-being of its citizens.

In a February 2020 speech, Prime Minister Boris Johnson dismissed the need for significant responses to Covid-19, emphasizing the importance of maintaining free trade despite the emerging pandemic. His rhetoric underscored a refusal to heed warnings from China and other countries already battling the virus, exemplifying a sense of British exceptionalism. Johnson's portrayal of the UK as a "supercharged champion" of free market principles, willing to eschew stringent health measures to avoid economic disruption, highlighted an overconfidence in British resilience and a dismissal of international examples and expert advice.

Contrary to global trends, the UK allowed mass gatherings to continue for longer than many other countries. For example, while the Chinese Super League was suspended in January 2020 and Serie A games were held behind closed doors from February, the UK permitted large-scale events until mid-March. During the same period, various countries across Europe starting to enforce lockdown measures like school closures, isolation and social distancing.

In one notable instance, Liverpool hosted Atletico Madrid at Anfield on March 11th, welcoming thousands of fans from Madrid, despite the city being under partial lockdown. During the same week, the Cheltenham Horse Racing festival attracted 251,000 attendees over three days. Regions hosting these events subsequently witnessed dramatic spikes in Covid-19 symptoms, turning into hotspots.

By March 12th, Johnson acknowledged that Britain was confronting “the greatest public health crisis for a generation.” However, he showed reluctance to adopt measures taken by other countries, such as closing schools or isolating the elderly. Instead, Johnson's administration gravitated towards a strategy of “herd immunity,” which would require around 60% of the population to contract Covid-19. This strategy was met with significant criticism from public health experts.

Johnson's steadfast belief in British exceptionalism led him to overlook lessons and advice from China and European neighbours. When later questioned about the UK’s higher death toll compared to countries like France and Germany, Johnson suggested it was due to the UK being more “freedom-loving” than its European counterparts. Even a higher death toll was taken as evidence of British superiority in some domain.

The UK government's refusal to heed advice or lessons was not just limited to its Chinese and European counterparts. It also consistently disregarded guidance from the World Health Organisation (WHO). For example, in February 2020, the WHO advised countries with imported cases or outbreaks to prioritise exhaustive case finding, immediate testing and isolation, and rigorous quarantine of close contacts. Despite this, the UK's response to contact tracing was slow, and initial efforts were abandoned in mid-March 2020.

In another notable departure from international consensus, the UK chose to develop its own ‘world-beating’ contact-tracing app, opting for a centralised model contrary to the decentralised systems adopted by Apple and Google. This decision, driven by a desire to be distinctive, encountered critical technical challenges and ineffectiveness across different smartphone platforms, resulting in a non-functional app. Ultimately, the UK adopted the decentralised approach used globally and adopted the same technologies as other countries, but this shift came with costly delays, highlighting the drawbacks of prioritising national distinction over practicality in a health crisis.

The UK government's obsession with being unique and world-leading was also evident in other aspects of its pandemic response. Led by Boris Johnson, the government seemed to view the crisis as an opportunity to showcase British superiority. In the early stages, the UK used international comparison graphs in daily briefings, initially indicating a lower death toll compared to other countries. This was largely the result of the virus arriving later in the UK. Consequently, as the UK caught up and surpassed its European neighbours, this feature was discontinued and officials admitted that the comparison charts could be misleading.

The UK government's stance towards the EU was notably adversarial throughout the pandemic period. It declined to join collaborative procurement efforts with other European nations. Instead, it sought to secure superior terms with individual vaccine manufactures. leading to disputes over vaccine contracts. This tension stemmed from AstraZeneca's ingredient shortages at its factories in both London and the Netherlands. Despite having agreements to supply vaccines to both the EU and the UK, AstraZeneca found itself in a bind, unable to fulfil both commitments. Each contract required AstraZeneca to make a “best reasonable effort” to deliver a specified quantity of vaccines. However, the company struggled to meet these obligations and seemed to prioritise its UK contract, exporting vaccines from EU-based factories to the UK but not the other way around.

This imbalance led the EU to suspect that the Johnson government was interfering with exports from the London facility, prompting the EU to restrict vaccine exports from its member countries. Eventually, the EU sued AstraZeneca, demanding the delivery of 120 million doses. On June 18, 2021, a court ruled that AstraZeneca had failed to uphold its contract, ordering it to deliver an additional 50 million doses to the EU by September 27, on top of the 30 million already supplied.

Despite the validity of the EU's grievance with AstraZeneca, British politicians and media often framed the EU's enforcement of its contract as an attempt to hijack ‘British’ vaccines. In a controversial move, Boris Johnson instructed security services to plan a military operation against an AstraZeneca vaccine facility in the Netherlands. This proposal, if executed, would have breached Dutch sovereignty and international law, potentially leading to severe diplomatic consequences, including sanctions and political and economic repercussions. Johnson's approach seemed to imply that while the UK's territory, sovereignty and its contractual rights with vaccine manufacturers were inviolable, the same did not apply to other nations. This attitude suggested a view of the Netherlands as a subordinate state, less significant than the UK.

This pattern extended into the latter half of the pandemic, particularly in the presentation of the UK’s vaccine programme. Johnson claimed that Brexit facilitated the UK's swift authorisation and deployment of vaccines. In reality, the UK utilised an emergency use authorisation process permissible under EU rules, similar to the approach taken by Hungary. While this method allows for faster national responses, it is less comprehensive than the EU European Medicines Agency (EMA) process. Additionally, under the standard EU authorisation, liability typically remains with vaccine manufacturers for any adverse effects, but the UK government assumed some liability to expedite vaccine authorisation. Ultimately, these steps enabled the UK to authorise the first vaccine 19 days before the EMA.

Similarly, the UK's approach to vaccine deployment was characterised by a willingness to take risks. Notably, the UK extended the interval between the first and second doses of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine beyond the manufacturer's recommendation, aiming to provide broader coverage more rapidly. This decision raised concerns about efficacy and the risk associated with partially vaccinated individuals as such an approach had not been empircally validated.

Despite these risks, the UK's vaccine rollout was relatively successful. However, Johnson often inaccurately claimed that the UK had the fastest vaccine booster rollout in Europe. For Johnson and those he appealled to, it was not good enough to have successful vaccine rollout, it was also neccessary to assert superiority. The UK likely reached the 70% herd immunity level recommended by experts after many of its European neighbours.

Allies of Boris Johnson claimed that his government "got all the big calls right" throughout the pandemic. However, this assertion has been contradicted by various analyses and reports. The UK experienced one of the highest COVID-19 mortality rates in Western Europe, particularly in the early stages. The number of deaths during the pandemic was 3.1% higher than the average of the previous five years, as reported by the Office for National Statistics (ONS). While some Central and Eastern European countries with less developed infrastructure fared worse, the UK's excess death rate was higher than that of Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Finland, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Luxembourg, Malta, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland. Italy was the only major Western country hit harder, primarily because it was the first European country to face the outbreak. Economically, the UK experienced a deeper trade decline during Covid and a slower recovery than almost all of its peers.

Throughout the pandemic, the UK government framed its response as leading the global fight against the virus, often using terms like "world-leading" and "world-beating" to describe its strategies. This focus on outperforming other nations stemmed from a belief in the need to demonstrate British superiority. There was a widespread refusal to learn from other countries or to take advice from international organisations. This mindset was not only evident in the government's actions and statements but also found acceptance and tolerance within the broader British establishment, including the press and opposition politicians. To this day, when asked to name a benefit of Brexit, Conservative politicians and columnists claim that the British response to the pandemic was superior, contrary to the available evidence. British exceptionalism, or at least the acceptance of some of its associated assumptions, appeared to be widely tolerated among the British establishment.

Case Study 3: Self-ID in Scotland

The landscape of gender identity and recognition in the United Kingdom, especially in Scotland, offers a compelling case study that highlights two components of British exceptionalism; firstly the peculiarly English nature of this brand of exceptionalism and a refusal to accept evidence from non-British jurisdictions as having relevance to the United Kingdom.

Before discussing the specifics of the case, we will provide some context to the issue. Research indicates that transgender individuals experience higher rates of depression and anxiety. The suicide risk among transgender people is particularly alarming, with the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention and the Williams Institute reporting that 41% of transgender and gender nonconforming individuals attempt suicide at some point in their lives, a rate nearly nine times higher than the national average. The causes and correlates of poor mental health in the transgender population are many and varied, including dysphoria experienced due to a mismatch between gender identity and physical appearance, and marginalisation, discrimination, and stigmatisation. Experiencing gender identity microaggressions, such as misgendering, is associated with increased feelings of hopelessness, suicidal ideation, withdrawal, and maladaptive coping strategies associated with poor mental health.

Health experts and organisations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, the World Health Organisation and the American Psychiatric Association. This includes not only medical interventions like hormone therapy and surgeries but also psychological support and social services. They advocate for the elimination of barriers to such care, emphasising that gender-affirming treatments are not elective but rather essential healthcare services. Studies consistently demonstrate that gender-affirming care significantly improves the quality of life, mental health, and overall well-being of transgender people. It has been shown to reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety, lower the risk of suicide, and improve self-esteem and body image. A study in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that in people aged 13 to 20 years, receipt of gender-affirming care, including puberty blockers and gender-affirming hormones, was associated with 60% lower odds of moderate or severe depression and 73% lower odds of suicidality over a 12-month period.

Self-identification plays a crucial role in gender-affirming approaches for transgender and gender diverse individuals. It centres on the principle that individuals are the best authority on their own gender identity and should have the right to declare their gender without the need for medical or psychological approval or intervention. This concept is fundamental to respecting and recognising the autonomy and dignity of transgender individuals. Self-ID ensures that transgender people are less likely to encounter some of the microaggressions and misgendering associated with depression and suicidal ideation. Self-ID is more than just an administrative procedure; it is a fundamental aspect of gender-affirming care and respect for transgender individuals. It empowers them to live authentically and more safely in a society that recognises and values their identity, and it plays a critical role in their psychological well-being and social integration.

The Gender Recognition Act of 2004 was a landmark in UK legislation, creating a legal framework for transgender individuals to change their legal gender. Effective from 2005, it was a response to align UK law with the European Court of Human Rights' rulings, acknowledging the violation of rights in preventing trans people from altering their birth certificate sex.

The act's key feature was the Gender Recognition Certificate (GRC), which granted legal recognition to the acquired gender of applicants and introduced measures to protect the privacy of transgender individuals. Despite its forward-thinking nature, the GRA soon attracted criticism for its procedural rigidity and medicalisation of the gender transition process. The Women and Equalities Committee's comprehensive review in 2016 highlighted these issues. The Scottish Government, aligning with the Committee’s findings, proposed reforms to mirror international best practices, including the elimination of requirements for medical evidence and a two-year living period in the ‘acquired’ gender.

In 2017, further demedicalisation of the GRA and a focus on self-identification gained momentum. Public support grew for removing the need for a diagnosis of gender dysphoria and a medical report. However, the UK government, diverging from these progressive views, chose to maintain the status quo. Scotland’s approach to gender recognition sharply contrasted with Westminster. The Scottish Government’s proposal to simplify the gender recognition process and align with evolving international norms reflected a progressive stance on transgender rights, including removing the gender recognition panel, lowering the age limit to 16, and abolishing the requirement for a diagnosis of gender dysphoria.

In a significant display of solidarity and advocacy, the bill garnered widespread support from feminist, LGBT, and human rights organisations, including Amnesty International, Stonewall, Rape Crisis Scotland, Equality Network, Engender, Scottish Trans Alliance, and Scottish Women's Aid. These organisations, known for their staunch commitment to human rights and equality, lent their influential voices in favour of the bill. The bill also received robust political backing. The majority of parliamentarians from the SNP and Scottish Labour, along with all Scottish Green and Scottish Liberal Democrat MSPs, supported the bill, demonstrating a rare moment of relative unity across different political spectrum.

The Westminster Government's aggressive response to Scotland's introduction of self-ID in the Gender Recognition Reform Bill was notable. For the first time, the UK government invoked Section 35 of the Scotland Act 1998 to block the Scottish bill on gender recognition. This action was based on concerns that the Scottish gender recognition bill would negatively impact women and disrupt the consistency of laws across the UK. The broader UK approach remained conservative, resistant to modifying existing laws despite significant public support and international trends favouring less medicalised, more self-determined models of gender recognition. This resistance starkly contrasts with Scotland's proactive stance.

The self-ID debate in the UK is contentious, particularly around the safety of cisgender women in single-sex spaces. Critics argue that simplifying the gender identification process could potentially allow predatory behaviour in women-only services. This concern extends to shelters, health facilities, and changing rooms. Somewhat bizarrely, the British debate often ignores the experiences of over 20 countries, including Argentina, Belgium, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Denmark, Ecuador, Finland, Iceland, Ireland, Luxembourg, Malta, New Zealand, Norway, Pakistan, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, and Uruguay, where progressive self-ID laws have been implemented without an increase in victimisation of women and girls. This disregard for international experiences exemplifies British exceptionalism, where the relevance of these global examples to the UK is bizarrely overlooked.

Instead of examining the results of policy changes in these countries, UK government Ministers drew up a blacklist of countries where they believed obtaining a GRC was too easy. Consequently, their GRCs would no longer be recognised while they were in the UK.

By dismissing Scotland's efforts to align more closely with progressive international practices on gender identity, the UK government reinforces this notion of Anglo-British superiority and centralism, illustrating a reluctance to embrace a more pluralistic and inclusive approach that acknowledges and learns from the experiences and policies of both its own constituent nations and other countries worldwide. This divergence not only underscores the unique challenges faced by transgender individuals in different parts of the UK but also highlights a deeper, systemic issue: the predominance of an Anglo-centric viewpoint that often overrides common sense, empirical evidence and regional autonomy in the UK.

Conclusion

British exceptionalism, thrust into the limelight by Brexit, reveals a deeply entrenched belief in the UK's unique and superior global status, permeating both conservative and liberal viewpoints. This ideology has consistently been a double-edged sword, driving policies and attitudes that frequently lead to detrimental outcomes.

During the Brexit negotiations, the UK's approach was characterized by an expectation of special treatment from the EU, a misplaced confidence in its negotiating prowess, and a blatant disregard for established international norms. This overconfidence manifested in unrealistic demands for special arrangements and a fundamental misunderstanding of the EU's cohesive stance, which was mistakenly viewed as mere posturing rather than a principled position.

David Cameron's failed renegotiations and the subsequent referendum highlighted how deeply this exceptionalist mindset had permeated British political strategy. The belief that the UK could secure better terms through sheer assertiveness led to a disconnect between British expectations and EU realities, resulting in a fractured nation. The Leave campaign capitalized on these sentiments, promising a resurgence of sovereignty and global prominence.

The UK's handling of the Covid-19 pandemic further underscored the dangers of exceptionalism. A reluctance to learn from other countries, delays in implementing necessary public health measures, and a uniquely British approach to vaccine distribution led to one of the highest mortality rates in Western Europe and a slower economic recovery.

The controversy surrounding Scotland's Gender Recognition Reform Bill illustrated the adverse effects of exceptionalism once again. Westminster's dismissal of Scotland's progressive stance and its refusal to acknowledge the successful implementation of self-ID laws in over 20 countries reflected a persistent belief in the UK's superior judgment and moral standing.

This pattern of exceptionalism is not limited to these instances. The absurdity of claims like Tony Blair's assertion that the UK is "the greatest nation on Earth" has become a tolerated norm. This acceptance of grandiose statements fuels a tolerance for impractical ventures such as Boris Johnson's "world-beating" contact tracing app and the unrealistic expectations of Brexit negotiations. Whether in matters of gender self-identification or attempts to devise technological solutions for the Northern Ireland border, British arrogance allows politicians and journalists to dismiss the lessons learned by other nations, perpetuating the belief in the UK's unique and superior character.

This mindset, far from being harmless national pride, is a pervasive ideology shaping policy and public perception to the UK's detriment. It fosters unrealistic expectations and a sense of grievance when the UK is treated as an equal among nations, as seen in its attitudes towards Ireland during Brexit negotiations and the Netherlands during the Covid-19 pandemic. This exceptionalism undermines practical and cooperative solutions, promoting a narrative of superiority at the expense of genuine international collaboration. Internationally, the UK often resembles Boris Johnson in his school days, perceiving itself as exempt from the “network of obligations that binds everyone else.”