Chapter 3: Neoliberalism is Just Common Sense

Neoliberal beliefs are unjustified by evidence and the fallacies of neoliberalism lie at the heart of Brexit and the UK’s economic crisis

In 2018, amidst the fervour of Brexit negotiations, the UK government presented its Brexit Impact Report to outline the potential economic outcomes under various Brexit scenarios. This report, released before a ‘meaningful vote’ in the House of Commons on the Brexit Withdrawal Agreement, aimed to provide a clearer understanding of the economic implications of the UK’s departure from the EU. It emphasised the critical nature of future trade arrangements between the UK and the EU—its largest trading partner—in determining the economic impact of Brexit.

Previously, membership in the EU Single Market and Customs Union had provided the UK with the advantage of low trade barriers within the EU. This was to change. The report indicated that Brexit would damage British trade with the EU and projected that the extent of the damage which would depend on the future trade relationship yet to be negotiated. Crucially, the report also noted that while new trade agreements with non-EU countries and growth-promoting regulatory adjustments could alleviate some of the inevitable economic drawbacks, they were unlikely to completely counterbalance the negative effects of increased EU trade barriers.

In response to this, hard right pro-Brexit economists Roger Bootle, Julian Jessop, Gerard Lyons, and Patrick Minford put forth an alternative economic analysis. They argued for the dismantling of “damaging EU regulation” such as the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive and criticised “needless restrictions on labour market flexibility”. Similarly, the right-wing think tank, the Institute for Economic Affairs (IEA), in its alternate Brexit plan, denounced EU regulation as “damaging to growth” and advocated for a market-driven approach post-Brexit, free from EU's regulatory constraints.

Despite the wishes of many of these figures for a 'Clean Brexit', the final deal resulted in a replication of EU regulations across numerous sectors. The proponents of ‘Clean Brexit’ contended that the envisaged benefits of Brexit had been stifled, attributing the failure of Brexit benefits to materialise to government leaders lacking the right economic orientation. However, the scenario began to change with the rise to power of Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng.

Liz Truss was appointed as Prime Minister on September 6, 20221. On the same day, Kwasi Kwarteng assumed the role of Chancellor of the Exchequer. Both Truss and Kwarteng had longstanding associations with the IEA. Both shared the free market libertarian ethos shared by Bootle, Jessop, Lyons, and Minford. They wanted to realise a shared vision for a deregulated market economy that would finally unlock the benefits of Brexit.

However, the total embrace of this ideology by Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng brought about a series of unprecedented negative outcomes. The market viewed their mini-budget as ideologically driven, with indications of more tax cuts on the horizon further exacerbating the situation. The financial turmoil triggered by their mini-budget led to the resignation of both Kwarteng and Truss, marking the failure of their governance approach.

The ideology driving the views of the Brexit economists and the policies of the Truss administration is Neoliberalism—a political-economic doctrine emphasizing the value of private enterprise, free markets, and minimal state intervention. Its roots trace back to classical liberal thought, with a modern orientation towards a market-driven approach to economic and social policies. In the UK, neoliberalism has quietly morphed its ideological beliefs into what's widely accepted, in media and politics, as common sense, promoting privatisation, market-based solutions and harsh policies towards the unemployed and disabled. This shift has made its market-first approach seem natural, even though it's more about ideology than solid evidence, leading to deep social divides that are often overlooked.

This chapter delves into the origins, evolution, and contemporary manifestations of this ideology in the UK, particularly highlighting its influential proponents and the consequent policy shifts. We will explore the history of neoliberalism, its influential figures, its intertwining with Brexit, and the subsequent policy initiatives that emerged in the UK. We will demonstrate how neoliberalism has negatively impacted Britain and argue for the rejection of this harmful ideology. As we delve into the ideological underpinnings that have significantly influenced economic and political discourse in the UK, particularly in the context of Brexit, it's imperative to unpack the concept of Neoliberalism.

The Origins of Neoliberalism

Neoliberalism, is often seen as a reactionary movement to the state interventionist policies of the mid-20th century, has its roots deeply embedded in the soil of classical liberalism. The transition from classical to neoliberalism isn't a linear one, but rather a nuanced evolution that reflects the changing economic and political landscapes over time.

Classical liberalism championed the principles of individual freedom, private property, and free markets with limited government intervention. It emphasised the supposed inherent ability of markets to self-regulate and proposed that individuals, when left to their own devices, would act in ways that naturally promote societal well-being. The tenets of classical liberalism were grounded in Enlightenment values and a firm belief in the power and virtue of the individual.

Fast forward to the 20th century, the emergence of Neoliberalism came as a response to what its proponents saw as an overreach of state intervention in the economy, which was characteristic of the post-war era. Unlike classical liberalism, neoliberalism doesn’t merely advocate for free markets; it posits that market mechanisms should drive all aspects of society, including those areas traditionally controlled by government. It's a doctrine that seeks to extend market relationships far beyond the realm of commerce, infiltrating all corners of societal and individual activity. This school of thought gained momentum in the latter half of the 20th century, heavily influenced by the ideas of economists like Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman.

Friedman contended that social democracy and socialism inherently stifled individual freedoms and led to economic inefficiencies. He was particularly critical of price controls, high taxes, and welfare programs, which he viewed as detrimental to productivity and individual initiative. His ideas found resonance among conservative politicians, especially during the 1980s. Notably, Friedman served as an economic advisor to Ronald Reagan during his 1980 presidential campaign, and his ideas also influenced economic policies under Margaret Thatcher in the UK. In Free to Choose, a book aimed at the general public and co-written with his wife Rose, Friedman asserted, "The society that puts equality before freedom will end up with neither. The society that puts freedom before equality will end up with a great measure of both." This statement encapsulates his critique of social justice efforts and his optimistic conviction in the free market's ability to yield fair results, illustrating a fundamental belief in prioritising the freedom of capital to achieve both freedom and equality.

Hayek, an Austrian-British economist and philosopher, was a staunch defender of economically liberal ideas and was also known for his advocacy for minimal state intervention and a free-market economy. Like Friedman, Hayek was vehemently opposed to social democracy and socialism. He feared that central planning and economic control by the state would inevitably lead to totalitarianism. In his influential work, The Road to Serfdom, he argued against the dangers of central planning and state control over the economy claiming that “"Socialism in all its forms is contrary to freedom. ... Socialism means slavery." Hayek's teachings significantly influenced political figures like Margaret Thatcher, promoting a shift towards market liberalisation and reduced state intervention.

The Neoliberals’ ideas did not gain traction in a vacuum; rather, they were propelled by sophisticated networks of neoliberal think tanks and societies, notably the Mont Pèlerin Society, the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) and the the Atlas Network.

Founded by Hayek in 1947, the Mont Pèlerin Society served as an intellectual crucible for neoliberal thought, bringing together economists, philosophers, historians, and business leaders who shared a concern over the rise of collectivist governments. The society's foundational belief was that the road to tyranny was paved with government overreach, and it championed the restoration and preservation of free-market principles as an antidote. Through regular meetings and influential publications, the society cultivated a robust intellectual framework that critiqued Keynesian economics and state intervention, laying the groundwork for policy influence.

In the UK, the IEA emerged as a pivotal platform for neoliberal ideas, influencing both public opinion and policy. Founded in 1955 by Antony Fisher, a businessman inspired by Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom, the IEA championed free-market policies and became instrumental in shaping the economic agendas of Conservative governments. By producing accessible research and engaging with politicians and the media, the IEA effectively shifted the Overton window, making neoliberal reforms, including privatisation and deregulation, politically viable. The IEA is remarkably influential within the UK, appearing on the British media on average 14 times a day in 2023.

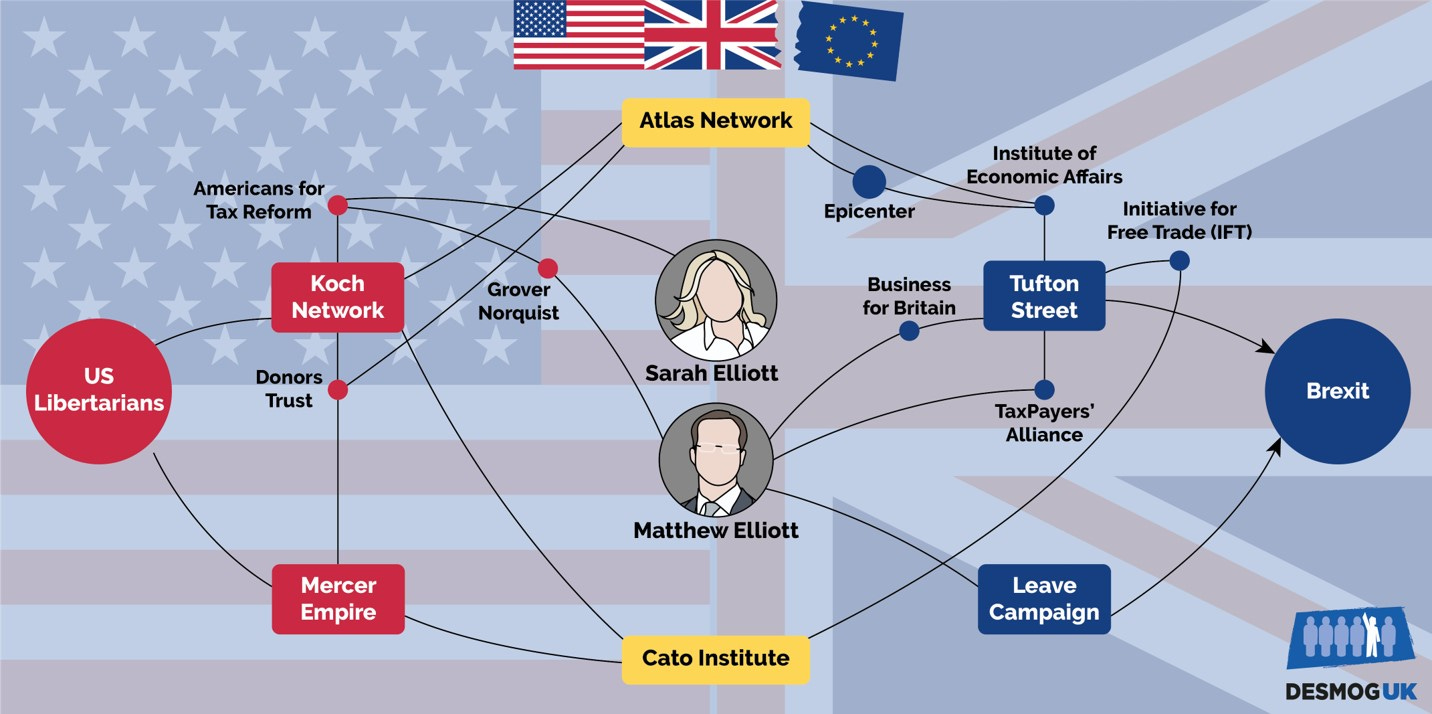

Globally, the Atlas Network, established in 1981, sought to replicate the IEA’s success by fostering a web of over 400 think tanks in more than 90 countries. This network has been pivotal in promoting neoliberal policies across diverse political and economic landscapes, facilitating the exchange of ideas, strategies, and resources among its members. Through conferences, training programs, and, most importantly, funding, the Atlas Network has amplified the reach of neoliberalism, influencing policy debates and reforms on every continent. In addition to the IEA, several other British think tanks are affiliated with the Atlas Network including the Adam Smith Institute and the Centre for Policy Studies.

Essentially, organisations such as the Mont Pèlerin Society craft the intellectual blueprints underpinning neoliberal ideology, whereas think tanks such as the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) aim to sway both political leaders and the public in favor of neoliberal policies. Meanwhile, networks like the Atlas Network serve to foster the growth of neoliberal think tanks globally and synchronise their activities, ensuring a coordinated approach to promoting neoliberal policies. The cumulative impact of these organizations, underpinned by the intellectual legacies of Hayek and Friedman, cannot be overstated. They have not only advanced the theoretical underpinnings of neoliberalism but have also played a critical role in its practical application across the globe. By framing neoliberal policy solutions as common-sense responses to economic and social issues, these think tanks and networks have shifted mainstream economic thought and influenced the policy direction of countless governments.

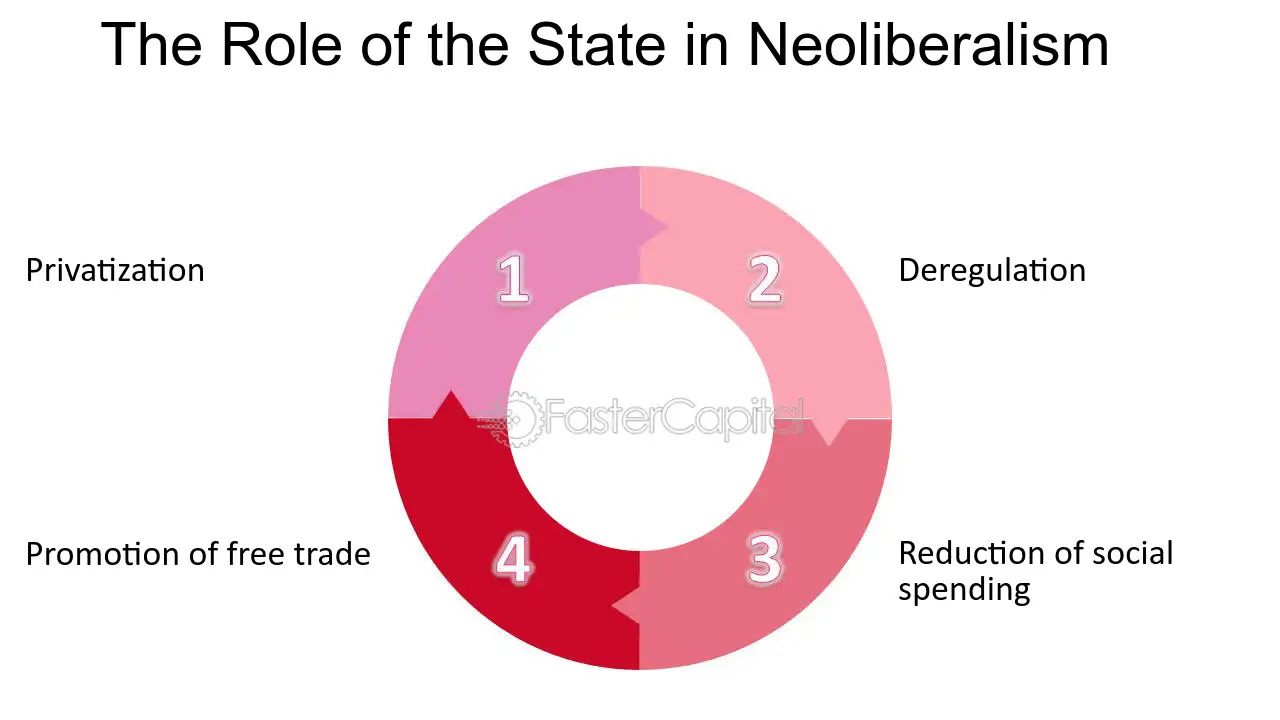

Neoliberal Beliefs

At its core, neoliberalism advocates for a retraction of state involvement in the economy and an enhancement of the role of market mechanisms and private enterprise in societal organization. This ideological stance permeates a wide array of policy domains, from social welfare and labor markets to healthcare, education, and beyond, fundamentally shaping the approach to governance and social welfare in contemporary societies.

Neoliberals generally advocate for reducing dependency on state aid in the form of disability or unemployment benefits. They argue that extended dependency on social welfare can deter individuals from seeking employment, leading many neoliberals to champion policies mandating work or active job searching as prerequisites for receiving benefits. They often prefer targeted assistance over universal schemes, providing support only to those in dire need.

While not all neoliberals advocate for the complete elimination of welfare programs, there's a strong emphasis on reforming these programs to enhance their efficiency, effectiveness, and sustainability, reflecting the broader neoliberal ethos of promoting personal responsibility, market efficiency, and minimal government intervention.

Privatisation, especially in sectors like healthcare and education, is another hallmark of neoliberal thought. The conviction is that private entities can deliver these essential services more efficiently and at lower costs compared to government-run systems. By fostering competition, neoliberals believe that privatisation can spur innovation, enhance service quality, and manage costs effectively.

In the labour market, neoliberalism upholds the ‘freedom to contract’ principle, which traces back to classical liberal thought. This principle asserts that individuals should have the autonomy to enter into agreements or contracts without undue interference from government in the form of minimum standards. Neoliberals argue that market forces of supply and demand should determine wages, contending that such a framework will align wages with workers' productivity and skills. They believe that deregulating labour markets and reducing or eliminating minimum/living wage laws will lead to a more efficient allocation of resources, better job matching, higher employment levels, and economic growth.

This scepticism towards regulation extends to health and safety standards. Neoliberals argue that excessive regulations could impede business innovation and economic growth. While many recognise the necessity of some basic standards, neoliberal think tanks will often lobby for the reduction of standards with regard to work practices, food safety and qualifications.

On a global scale, neoliberalism's preference for national sovereignty and minimal government intervention often clashes with the supranational regulatory frameworks of entities like the European Union (EU). Neoliberals, following in the ideological footsteps of Hayek and Friedman, view the EU's central planning and regulatory harmonization sceptically, seeing them as restrictions on market freedom and individual choice.

Across these diverse aspects, the recurring theme is a pronounced preference for market mechanisms over government intervention, a belief in competition as a driver of efficiency and innovation, and a scepticism towards centralised planning and regulation. The moral dimension of neoliberalism is intertwined with a broader philosophical tradition that valorises individual liberty, market freedom, and a limited role for government as essential for fostering a just, prosperous, and morally upright society.

Neoliberals often view the outcomes of their policies through a moral lens, where deregulated labour markets, privatised services, and constrained state intervention are seen as inherent goods. Even when faced with adverse outcomes like lower wages, insufficient benefits, job insecurity, or poor service delivery in privatised sectors like rail or water, neoliberals may regard these as temporary challenges or necessary evils that are prices worth paying to uphold an economic system free from what they view as the tyrannical grasp of government intervention.

Neoliberalism places a profound emphasis on economic rights, often positing them as paramount over social or political rights. The core belief is that economic rights, epitomised by property rights and freedom to contract, form the bedrock upon which other rights and societal well-being are built. The fundamental notion is that safeguarding economic rights will naturally culminate in broader societal benefits.

It's believed that an unfettered market, driven by the economic rights of individuals, will lead to just resource allocation, innovation, and wealth creation which will, in turn, benefit society at large. This perspective often leads to a deprioritisation of social and political rights, especially when they are perceived to conflict with the core neoliberal value of economic freedom.

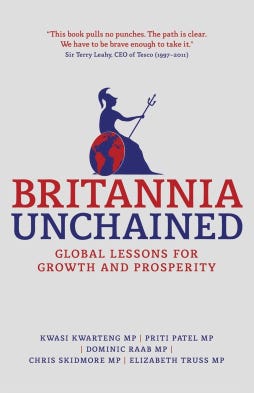

Britannia Unchained: A Manifesto of Neoliberal Ideology

Britannia Unchained: Global Lessons for Growth and Prosperity stands out as an important example of neoliberal ideology within the British context. Written by Kwasi Kwarteng, Priti Patel, Dominic Raab, Chris Skidmore, and Liz Truss, the book sought to redefine Britain's economic narrative by advocating for a radical revamping of existing policies. At its core, Britannia Unchained champions a neoliberal ethos of deregulation, fiscal austerity, and free-market capitalism. The authors argue for lower taxes, reduced public spending, and a rollback of employment laws and regulations—hallmark tenets of neoliberalism that prioritise market liberties over social protections. They critique welfare provisions, asserting that a so-called dependency culture has hampered economic growth—a viewpoint that aligns with the broader neoliberal narrative attributing economic malaise to welfare state expenditures rather than systemic market flaws.

The authors berate what they view as a culture of idleness among Britons, declaring that "Once they enter the workplace, the British are among the worst idlers in the world." They juxtapose this perceived lethargy against the industrious spirit seen in emerging economies and the innovative zeal of places like Silicon Valley. To accentuate their point, they assert, "Whereas Indian children aspire to be doctors or businessmen, the British are more interested in football and pop music." Through such juxtapositions, the authors underscore a perceived lack of ambition and productivity in the UK, advocating for a market-centric paradigm to propel the nation forward.

Despite its assertive tone, Britannia Unchained attracted a slew of criticisms. Sam Bright, writing for Byline Times, likened it to “a Hunger Games manifesto," envisioning a nation where workers are relegated to precarious, low-wage employment. He also criticised it for its imperial nostalgia, quoting the authors’ lamentation over Britain’s lost imperial confidence. Bright depicted Britannia Unchained as a reflection of the sort of Britain its authors wish to govern—a neo-imperial power keen on extracting economic output from national resources, heedless of the toll on workers.

Jonty Bloom, in a piece for The New European, rebuffed the book’s underlying premise that casts the UK as an international failure due to “soft, lazy, left-wing shirkers.” He further questioned the evidence supporting such claims, underscoring the book’s derisive tone towards British students, workers, and societal values. The book’s nostalgic undertones and its subtle allusion to a bygone imperial era have been pointed out by critics, arguing that this nostalgia, fused with libertarian ideologies, crafts an image of Britain anchored in colonial dominance, overlooking a forward-looking vision to address contemporary challenges.

Despite the poor reception of Britannia Unchained, each of the authors ascended to notable positions within the UK government, underscoring the resonance of neoliberal ideals within certain factions of the political establishment. Chris Skidmore was appointed Minister for the Constitution in 2016 and Minister of State for Universities, Science, Research and Innovation in 2018. Priti Patel was appointed Secretary of State for International Development in 2016, and later became Home Secretary. Dominic Raab became the Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union in 2018, and later became Foreign Secretary. However, it was Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwateng who ascended highest and brought Britain lowest.

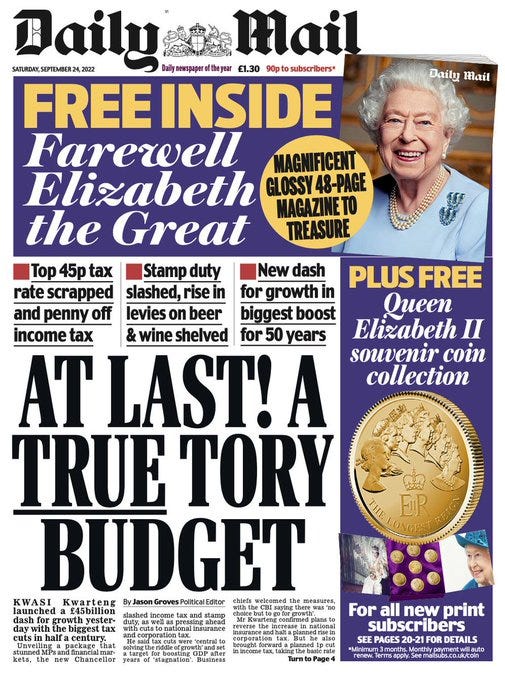

Trussonomics

In September 2022, Liz Truss assumed the mantle of Prime Minister and Kwasi Kwarteng was appointed as her Chancellor for the Exchequer. The pair proposed a controversial economic strategy that aimed to stimulate growth through significant tax cuts and deregulation, a plan often referred to as "Trussonomics". This strategy was outlined in a ‘mini-budget’ presented by Kwarteng in September 2022, which included plans for wide-ranging tax cuts, such as reversing a recent increase in National Insurance contributions, scrapping a planned rise in corporation tax, and abolishing the top rate of income tax for the highest earners. These measures were intended to boost investment, increase disposable income, and spur economic growth.

Enthusiasm from neoliberal think tanks and commentators was palpable following the announcement of the mini-budget. Allister Heath, the Sunday Telegraph editor, hailed it as the most significant of his lifetime, stating, "The tax cuts were so huge and bold, the language so extraordinary, that at times, listening to Kwasi Kwarteng, I had to pinch myself to make sure I wasn’t dreaming, that I hadn’t been transported to a distant land that actually believed in the economics of Milton Friedman and FA Hayek." Similarly, Patrick Minford from the Centre for Brexit Policy lauded Trussonomics as “not only credible,” but “vital.” Gerald Lyons of the Policy Exchange Think Tank praised the budget's potential to “boost growth,” asserting that “everyone will benefit.” Tim Montgomerie, founder of Conservative Home and a senior fellow at the Legatum Institute, saw the mini-budget as a pivotal achievement for the IEA, revealing that Truss and Kwarteng had been “incubated” by the IEA in their formative political years and that the organization had long championed these neoliberal policies. The IEA itself, through its Director Mark Littlewood, warmly received the budget, with Littlewood calling it “refreshing” and expressing eager anticipation for what he termed the ‘maxi’ budget, saying, “If this was the Chancellor’s ‘mini’ budget, I look forward to the ‘maxi’ budget.”

Outside of the neoliberal ecosystem, the reception was uniformly negative. The financial markets rejected ‘Trussonomics’ due to major concerns over the plan's sustainability and inflationary pressures. The proposed significant tax cuts, presented without a detailed funding strategy, stoked fears of increased public borrowing amidst already high inflation. This lack of fiscal clarity and the potential exacerbation of inflationary trends triggered a crisis of confidence, manifesting in a sharp sell-off in UK government bonds and a historic plunge in the value of the pound. Investors were particularly alarmed by the prospect of the government fueling demand without addressing supply constraints, raising the specter of higher interest rates to stabilise the currency and curb inflation, which in turn could harm households and the broader economy. This cocktail of concerns led to a rapid loss of market confidence in the UK's fiscal management.

On October 14th 2022, Truss dismissed Kwarteng and subsequently resigned six days later. Her reign, spanning a mere 6 weeks, is estimated to have cost the UK treasury £30 billion. Nonetheless, this episode did not deter Truss’ allegiance to neoliberal economics. She attributed the debacle of her policies to the "anti-growth coalition," the “deep state” and the left -wing “economic establishment”. The ensemble accused of constituting the "anti-growth coalition" included financial markets, opposition parties, trade unions, podcasters, vested interests masquerading as think tanks, the Just Stop Oil environmental group, trans activists, Tory party MPs, quangos, the Financial Times and panelists on BBC television and radio shows. It appeared Truss blamed anyone not vehemently endorsing neoliberal economics for the failure of her neoliberal agenda.

Despite the economic ravages of Trussonomics, the former-PM remained unapologetic, chastising her colleagues’ lack of allegiance and a left-wing “economic establishment” for her downfall. Similarly, many of those who had supported Truss and Kwarteng’s disastrous mini-budget continued to insist that she had the right ideas, but had executed them poorly Truss continues to appeal to the hard-neoliberal faction of her party by establishing the narrative that her ideas were right, but the timing was wrong . She recently appeared a “pro-growth rally” at the Tory Party conference and was welcomed with cheers.

Truss’ continued presence within the British political establishment and popularity with the base of the Conservative party is a testament to the resilience of the neoliberal movement in the UK. While her survival might confuse many, it is important to understand that Truss’ rehabilitation venture was abetted by neoliberal think tanks like the Heritage Foundation and billionaire-owned Tory newspapers. In subsequent sections, we will delve into what makes neoliberalism so attractive to the wealthy and explore how neoliberal think tanks mould policy to mirror neoliberal ideology.

The Appeal of Neoliberalism among the Affluent

The attractiveness of neoliberalism for the wealthy is intricately tied to its core tenets which accentuate economic freedom, minimal state intervention, and the sanctity of private property. This ideological framework invariably serves the interests of those with substantial economic resources, providing both a practical and a moral scaffolding for perpetuating wealth and influence.

One of the central features of neoliberalism is its advocacy for a ‘minimal state.’ This proposition is particularly appealing to the wealthy as it often translates to lower tax liabilities. Unlike average earners, the single largest item of expenditure for the wealthy is tax and so the fewer the services provided by the state, the less tax revenue is required to fund those services. Simultaneously, the withdrawal of the state from various sectors opens up lucrative opportunities for private enterprises to step in and fill the void. The wealthy, with their substantial capital reserves, are uniquely positioned to invest in and profit from these newly privatised domains, be it healthcare, education, or public utilities. The market-centric ethos of neoliberalism thus creates a fertile ground for the wealthy to further augment their wealth and economic influence.

Moreover, the neoliberal emphasis on economic rights - notably property rights and the freedom to contract - effectively amplifies the freedom of those with more financial resources. In a system where economic rights are paramount, having more capital essentially translates to having more freedom. This structure, while ostensibly neutral, inherently favours the wealthy, enabling them to navigate and exploit society to their advantage. For example, cutting inheritance tax, benefits those due to inherit one million pounds more than it does those due to receive twenty thousand. The moral rhetoric of neoliberalism often veils the systemic inequities it engenders, portraying the resulting economic hierarchy as a neccessary, natural or deserved order.

The moral dimension of neoliberalism provides a veneer of legitimacy to these economic arrangements. By framing market freedom and minimal state intervention as moral imperatives required to avoid socialist totalitarianism and slavery, neoliberalism offers a moral justification for the wealthy to engage in practices that perpetuate or even exacerbate economic disparities. The ideological narrative posits that unfettered markets are not just economically efficient, but also morally righteous, effectively sanctifying the economic privileges of the wealthy.

Through a combination of reduced tax liabilities, lucrative investment opportunities in privatised sectors, and a moral narrative that venerates market freedom and justifies inequalities, neoliberalism effectively serves as both a vehicle and a shield for the affluent in their pursuit and preservation of wealth and influence.

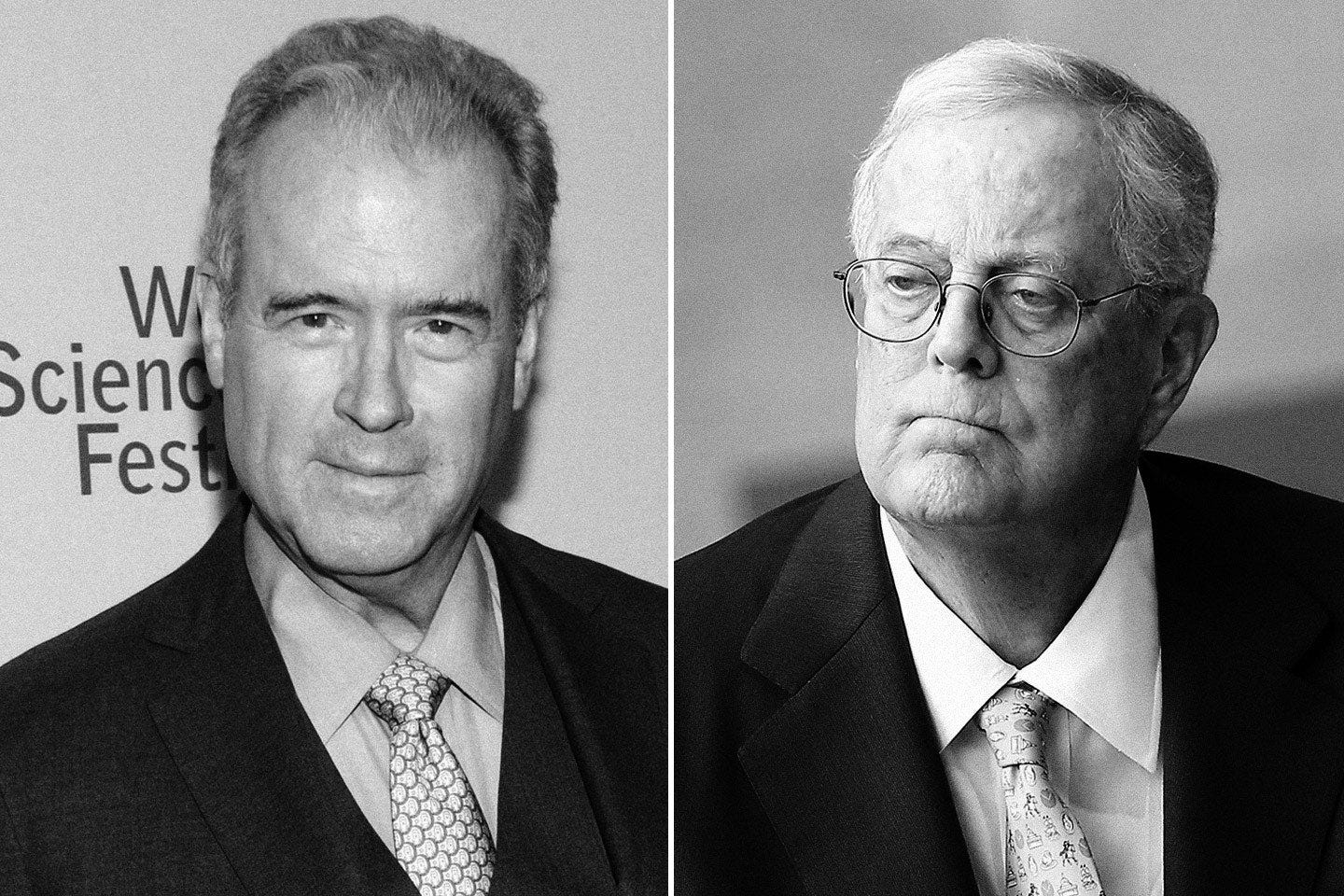

Billionaire Funding for Neoliberal Lobby Groups

The myriad of societies, think tanks, media organisations and networks which constitute the neoliberal ecosystems could not function without funding provided by wealthy patrons. This dependence means that while the ideological roots of neoliberal think tanks trace back to Hayek and Freedman, many specific policies can be traced back to wealthy donors like the Koch and Mercer families. Their financial backing significantly shapes the ideologies and operations of these think tanks, which in turn, wield considerable influence over UK- policy-making and media narratives.

For example, the Global Warming Policy Foundation (GWPF), a UK-registered charity, states it avoids energy company funds. Yet, it's funded via the Donors Trust, which channels donations from wealthy individuals, including the Koch family, to preferred causes. The Kochs, with significant oil interests, have funneled $864,884 to GWPF through this trust. This method allows GWPF to maintain a veneer of neutrality while opposing net-zero policies and supporting fracking, actions that align with the Kochs' business interests.

In a manner akin to how the Kochs utilize Donors Trust, the Mercer family funds the Cherish Freedom Foundation, which in turn supports the Centre for Policy Studies (CPS), a think tank founded by Margaret Thatcher. This funding influenced the Conservative Party's 2019 manifesto, authored by CPS members, and bolstered Liz Truss's leadership bid. Moreover, the Mercers' support extended to Brexit, employing their firm Cambridge Analytica to help deploy targeted pro-Leave advertising, showcasing their significant impact on UK political dynamics.

Matthew Elliott is a central figure in the neoliberal network, skillfully connecting political strategy, think tank philosophies, and funding tactics. He founded the TaxPayers' Alliance, advocating for lower taxes and fiscal openness, thus drawing support from neoliberal circles and establishing connections with conservative leaders and business magnates. His creation of the Politics and Economics Research Trust and Big Brother Watch aimed to deepen neoliberal discourse across economic policies and civil liberties. As Vote Leave's Chief Executive, he led the charge against EU membership, viewing it as a financial burden on the UK, and participated in initiatives promoting fossil fuel interests, including the All Party Parliamentary Group on Unconventional Oil and Gas.

Through a lens of neoliberalism, Elliott’s think tanks crafts a narrative that unites seemingly separate causes such as climate change scepticism and Brexit advocacy, in a way that typically serves the interests and preferences of billionaire donors. They frame domestic environmental regulations and broader EU directives—especially those that could dent profit margins—as violations of fundamental economic liberties. The selection of causes these think tanks advocate for, and those they conspicuously ignore, merits scrutiny. For instance, Elliott's Taxpayer’s Alliance is quick to denounce public sector strikes, citing concern for taxpayer value, yet remained conspicuously silent on the wasteful expenditure of billions in taxpayer money through crony contracts for Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) during the Covid-19 pandemic. His Big Brother Watch has outspokenly criticised financial monitoring by banks and authorities as invasions of privacy, yet it has turned a blind eye to governmental anti-protest laws aimed at quelling environmental activism. Moreover, Elliott’s Politics and Economics Research Trust displayed a stark bias in 2014, allocating 97% of its £532,000 in grants to pro-Brexit entities, with not a penny for Pro-EU organizations. This pattern of selective advocacy reveals a complex web of influence and priorities that shapes the public discourse to suit a specific agenda, one that is not solely based on neoliberal ideology, but also on donor interests.

Today, 55 Tufton Street, near Westminster, serves as a hub for various right-leaning organisations advocating for pro-Brexit, deregulation, and free-market policies, with notable sway over the Conservative party. Tufton Street associated organisations include TaxPayers’ Alliance, the IEA, Policy Exchange, the Adam Smith Institute, and the Legatum Institute. In other contexts, it might make sense for these organisations to amalgamate and share resources. After all, they are practically ideologically identical. However, the sheer number of supposedly independent think tanks calling for neoliberal policies enables the movement to shift public opinion more easily. It enables neoliberals to position their preferred policies not as neoliberal ideology, but as a consensus, commonsense position.

The British media serves as a vital channel for these think tanks to disseminate their research and narratives. Employees of think tanks, frequently treated as experts by the British media, frequently provide commentary and analysis in media outlets. However, media outlets frequently fail to identify the financial interests of think tanks. Indeed, much of the time, said think tanks refuse to reveal the source of their funding. In effect, biased lobbyists are allowed to share ‘research’ findings and opinions as though they were neutral experts, misleading the public. This is unfortunate situation is not entirely accidental. Much of the British media is billionaire owned and such wealthy patrons are sympathetic to the messages of neoliberal.

The intricate web connecting think tanks, media, and government in the UK is vividly illustrated through figures like Timothy Montgomerie, a linchpin between Conservative speechwriting and foundational roles in Conservative Home and the Centre for Social Justice, who also lends his voice to leading newspapers. Fraser Nelson, steering The Spectator, intertwines with the Centre for Policy Studies, mirroring Robert Colville’s dual engagement with the same think tank and journalistic contributions, notably to the Sunday Times and advising Liz Truss’s government. This revolving door, facilitated by affluent backers, crafts a conduit for advisory and journalistic influencers to cyclically penetrate governmental policy-making. While in the media and governmental discourse, the voices of wealthy donors with neoliberal leanings are prominently featured, the broader public's interests often remain underrepresented.

Debunking Neoliberal Myths: Lessons from Scandinavia

Neoliberalism, characterised by its staunch advocacy for market deregulation, minimal state intervention, and a laissez-faire economic stance, posits that these elements are crucial for a nation's economic prosperity and the freedom of its citizens. However, a closer examination of some of the world's prosperous and innovative nations unveils a different narrative, demonstrating that alternative models can not only function effectively but also thrive.

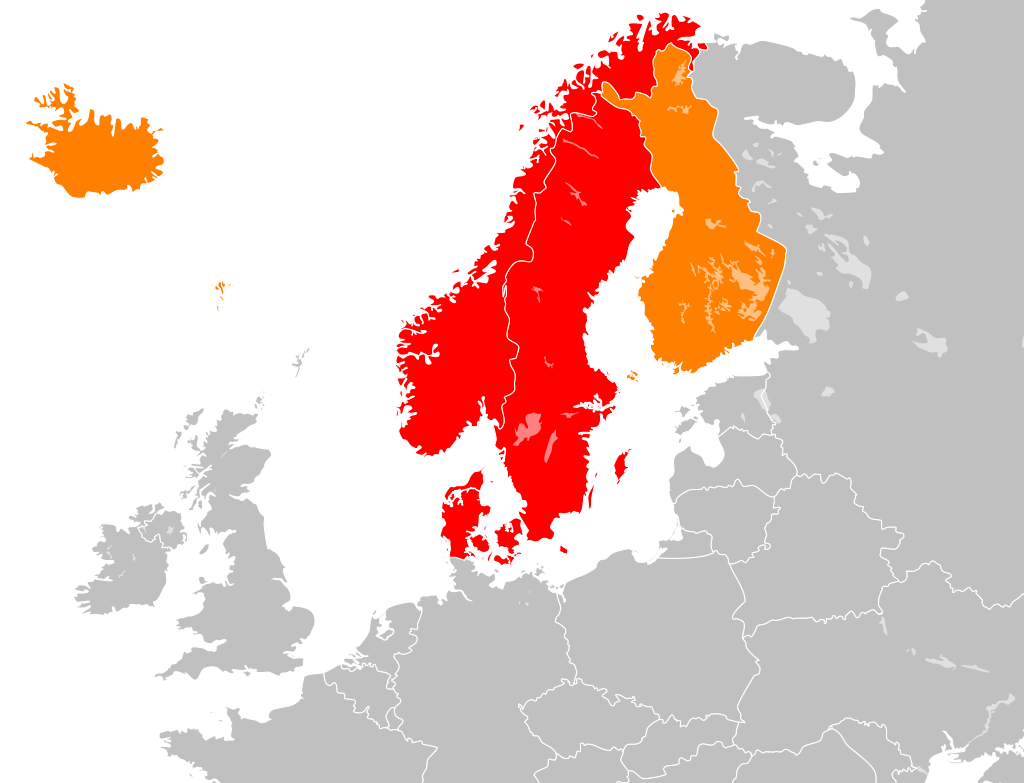

The Scandinavian countries - Sweden, Iceland, Denmark, Norway, and Finland - stand as prime examples that challenge numerous neoliberal assumptions. Despite their endorsement of social welfare, rigorous regulations, and state intervention in key sectors across generations, these nations have attained remarkable levels of prosperity, innovation, freedom, and social equality, often matching or surpassing the performance of the US and UK where neoliberal ideas have had a significant influence.

Neoliberalism frequently argues that substantial unemployment benefits serve as a deterrent for job-seeking. However, the Scandinavian countries, recognized for their strong social safety nets, maintain unemployment rates that are competitive with, or even lower than, those of the US and UK. For instance, in September 2023, Denmark's unemployment rate of 4.2% was lower than the UK's 4.3%, and comparable to the US's 3.8%. This outcome can be credited to their active labor market policies which, besides offering financial support, extend training and re-skilling opportunities for job-seekers, thus promoting a more efficient alignment between employers and prospective employees.

Neoliberal opposition to ‘over-regulation’ is rebutted by the thriving entrepreneurial climate observed in these nations, notwithstanding their stringent regulatory frameworks. Their ease of doing business rankings are compelling. While the UK placed 8th, Denmark (4th), Norway (20th), and Finland (11th) all positioned within the top 20, demonstrating that well-considered regulations can coexist with a buoyant business atmosphere, propelling innovation and competition.

Despite the neoliberal reluctance towards media ownership regulation, ostensibly to protect press freedom, countries with more stringent regulations on media ownership often secure higher positions on press freedom indices. This is exemplified by the dominance of Scandinavian nations within the World Press Freedom Index. Norway (1st), Denmark (3rd), Sweden (4th)m Finland (5th) and Iceland (18th) significantly outperform the more neoliberal US (47th) and UK (35th). By averting a concentration of media ownership, these countries ensure a diversity of voices and perspectives, fundamental for a robust democracy.

The high levels of innovation and global competitiveness displayed by Scandinavian countries defy the neoliberal mantra of state intervention being anathema to innovation. For instance, Sweden ranks 2nd, Denmark 9th, and Finland 6th on the Global Innovation Index, indicating that through smart investments in education, research, and technology, these nations have created conducive ecosystems for innovation and entrepreneurship.

Drawing from the compelling evidence showcased by Scandinavia and other similarly governed nations, it becomes abundantly clear that the neoliberal framework isn't the exclusive pathway to economic and social triumph. These nations champion a distinct narrative—one that esteems social cohesion, equality, and a balanced approach to market regulation and state intervention, thus cultivating environments where prosperity, innovation, and freedom harmoniously coexist.

The Scandinavian example eloquently argues for a nuanced approach that intricately interweaves market dynamics with social welfare, challenging the rigid neoliberal dichotomy between economic prosperity and social welfare. Yet, zealous neoliberals often dismiss the success of social democratic countries like the Scandinavians as illegitimate, harbouring a belief that their envisaged freedom—freedom of capital—supersedes all other liberties.

Even when faced with undeniable metrics of Scandinavian success, their rigid, dogmatic ideology blinds them to alternative, effective models of governance, leading to a dismissal of achievements attained through means they deem heretical This unfounded denial not only undermines a wealth of evidence but also stifles the potential for adopting a more balanced, inclusive approach towards economic and social governance that can foster a thriving, equitable society.

Debunking Neoliberal Myths: Lessons from Britain

The UK's experience with neoliberal policies, particularly the push for deregulation and privatisation, offers a complex picture that often contradicts neoliberal promises of increased efficiency and prosperity for all. Firstly, the privatisation of key industries, such as the railways and utilities, has not always led to the touted improvements in service or reductions in costs. Instead, many have witnessed rising prices and declining service quality, suggesting that profit motives can sometimes conflict with public interest.

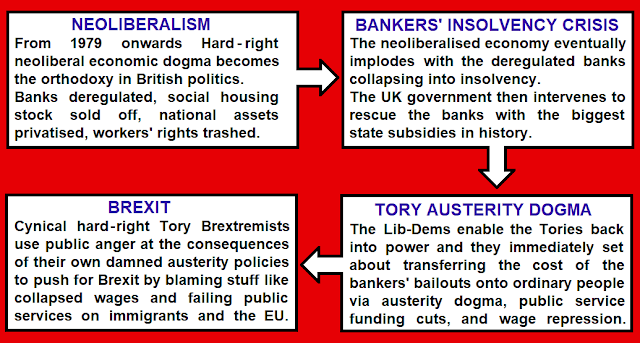

Secondly, the neoliberal deregulation of the financial sector, celebrated for promoting innovation and growth, played a significant role in the 2008 financial crisis. The lack of stringent oversight and accountability enabled risky financial behaviours that had global repercussions, highlighting the dangers of unfettered market freedom. Furthermore, the austerity measures implemented in the aftermath, while grounded in neoliberal ideology to reduce government spending, have had profound impacts on social services and welfare. These cuts have often disproportionately affected the most vulnerable in society, contradicting claims of neoliberalism fostering general welfare.

The NHS's challenges with privatisation efforts provide another critical example. Attempts to introduce market mechanisms into healthcare have raised concerns about the erosion of universal care principles and increased inequality, indicating that some public goods may not be suitable for market-based approaches.

Lastly, the UK's housing market, marked by deregulation and privatisation tendencies, has seen affordability and access issues exacerbate. This situation underlines the argument that certain essential sectors, when left predominantly to market forces, fail to ensure equitable outcomes for all citizens.

The unfolding of neoliberal policies in the UK, particularly through deregulation and privatisation, starkly contrasts with the optimistic visions heralded by figures like Milton Friedman, who famously argued that prioritising freedom over equality would yield abundance in both. Yet, the reality has diverged significantly from such neoliberal propaganda. The expectation that unfettered markets would naturally lead to optimal societal outcomes has not been met. Instead, these policies have often exacerbated inequality and neglected the public welfare, underscoring a profound disconnect between neoliberal ideals and their implementation outcomes.

Concluding Thoughts

As we wrap up this chapter, the negative impact of neoliberalism on UK society should be clear. From the Brexit quagmire to the calamitous missteps of the Truss administration, extending to the harsh treatment of benefits claimants and the privatisation wave, neoliberalism has played a detrimental role in UK life.

The trajectory of Thatcherite neoliberal policies in the UK encapsulates a cyclical pattern of ideological persistence despite adverse outcomes. These policies laid the groundwork for the 2008 financial crisis, an event which then served as a pretext for further neoliberal austerity measures, ostensibly aimed at economic recovery but effectively diminishing state welfare and public services. Privatisation led to diminished service quality alongside increased costs for citizens, notably in housing and utilities, exacerbating public dissatisfaction. Yet, rather than questioning the neoliberal framework, public discontent was redirected by influential media networks towards scapegoats like EU regulations and immigration, both perennial targets of neoliberal criticism.

The Brexit campaign, steeped in neoliberal rhetoric, promised relief but ultimately failed to address the root issues. The subsequent economic turmoil under "Trussonomics" wasn't met with introspection from neoliberal proponents; instead, they doubled down, blaming an alleged left-wing economic establishment. This cycle of applying and then reapplying neoliberal solutions to problems often exacerbated by neoliberalism itself reveals an ideology driven more by faith than empirical evidence. Each failure, from Thatcher’s deregulation and privatisation, through austerity and Brexit, to Trussonomics, has been met not with reevaluation but with calls for even more neoliberal policies, underscoring the dogmatic nature of its adherence.

The ideologies propagated by Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek have enduringly permeated global policy-making, yet their widespread adoption appears less a testament to the ideologies' intrinsic merits of promoting liberty, efficiency, and prosperity, and more a consequence of opaque networks of neoliberal influence. This dissemination, often shadowed by the financial backing of affluent elites, raises questions about the true beneficiaries of neoliberal policies. Increasingly, it seems that these ideas principally advantage the already wealthy, casting doubt on neoliberalism’s promises of prosperity and freedom.

A thriving democracy depends on the active engagement and informed debate among its citizens. We need to cultivate a culture of open discussion, critical examination of prevailing ideologies, and academic inquiry. Establishing platforms for debate, encouraging academic exploration, and advancing civic education are vital to equip individuals to engage in nuanced policy discussions, beyond the narrow confines of discredited neoliberal ideology. The overrepresentation of shadily funded think tanks and their shoddy research within the media, combined with an unwillingness on the part of journalists to highlight conflicts of interests, stifles open, honest, objective and balanced debate. It’s only reasonable that when think tank representatives partake in public debates, their funding sources are disclosed to present the audience with a clear picture of any biases.

The contrasting scenarios painted by different economic models, notably the egalitarian frameworks of Scandinavia, are illuminating. A deeper dive into these alternative models and assimilating the insights can help shape a more balanced and equitable policy framework. Ignoring the lessons of other countries is not a mistake the UK cannot afford to make. In our interconnected world, global collaboration to address shared challenges and to learn from diverse economic models is indispensable. Engaging in cross-national studies, sharing best practices, and fostering dialogues to enrich the global policy discourse are steps towards a more collaborative and informed international community.

Neoliberalism is not, and never has been, an evidence-based approach. While neoliberal propagandists try to present it as mere common sense, the harmful results of both Brexit and Trussonomics demonstrate that neoliberal economics is not just wrong, but actively harmful. A shift towards evidence-based policy-making, will be essential if the UK is to avoid further blunders based on the neoliberal blueprint. This shift necessitates fostering a culture of rigorous research, data-driven analysis, and a readiness to adapt policy frameworks in light of new evidence and changing circumstances.

Challenging dogmatic approaches, nurturing ideological diversity, and promoting adaptability in policy-making will be central if the UK is to move towards a more inclusive and responsive governance model. The journey towards a more equitable and prosperous society is a continuous endeavor. It calls for a collective commitment to scrutinise, learn, and evolve – transcending ideological rigidity and embracing a pragmatic, evidence-driven approach to policy formulation.