Chapter 2: Some People are Better than Others - Aristocracy and the Class System

The ethos of the British class system is anchored in a deep-seated belief that merit is unevenly distributed by nature, fostering a collective mindset that accepts, and even celebrates, inequality

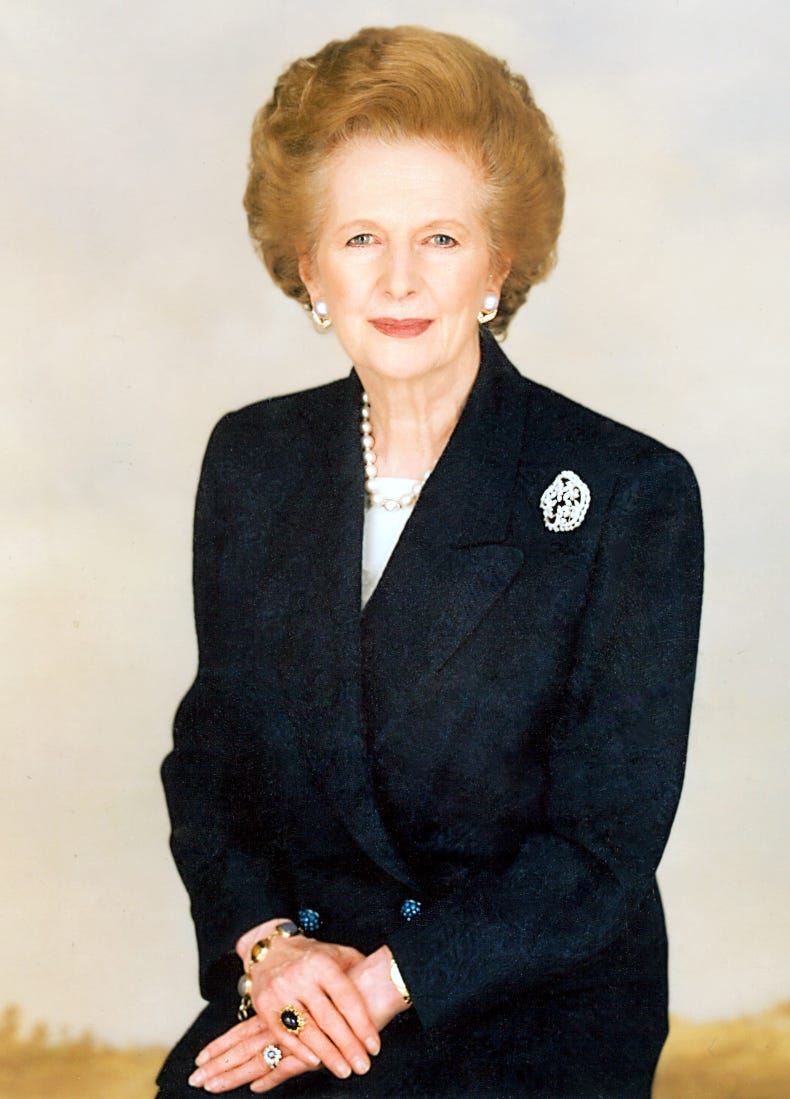

In the 1960s, political scientist Richard Rose poignantly observed that "In no society is social equality fully achieved; in England, it is often not valued as a goal," capturing the ambivalence towards social equality ingrained in British society. This sentiment was later epitomised in the 1980s by Margaret Thatcher, who famously stated, "Let our children grow tall, and some taller than others if they have it in them to do so," advocating a meritocratic vision that naturally elevates those deemed inherently superior. Contrasting Thatcher's ethos, Theresa May presented an ostensibly more inclusive vision, asserting, "Everybody living in this country is equal and everybody is free to lead their lives as they see fit," suggesting a commitment to equality. However, her tenure did not significantly address systemic barriers such as the advantages conferred by private education or the enduring influence of aristocracy in legislative processes. In truth, May was simply presenting Thatcher’s ideas in a manner that is acceptable to contemporary sensibilities.

These statements reflect a fundamental tension within British society: a proclaimed commitment to democratic equality juxtaposed against a deeply entrenched belief in the natural hierarchy of talent and worth. This contradiction is not merely rhetorical but embodied in the ongoing prominence of a traditional aristocracy that rules by heritage and a new aristocracy, privileged by private education and wealth, both endorsing inequality as natural and justifiable.

This chapter delves into the ideological underpinnings of this dichotomy, examining the mental gymnastics required to reconcile the belief in universal egalitarianism with the acceptance of inherent superiority among certain societal echelons. Through this exploration, we aim to shed light on the complex relationship between aristocracy, class, and the British socio-political landscape, revealing how these constructs perpetuate disparities that challenge the very essence of fairness and democracy.

Just How Unequal is the UK?

Imagine a society where your birth circumstances do not impact the course of your life. In a realm with full social mobility, offspring of affluent and impoverished families have equal shots at becoming either presidents or prisoners. But let’s snap back to the reality of the UK, where social mobility seems to be in short supply.

Among the G7 giants, the UK lags, tailing nations like Germany, France, Canada, and Japan in the Global Social Mobility Index. This data crafts an image of a somewhat stiff socio-economic framework, where rising to the top is as daunting for the disadvantaged as tumbling down is improbable for the wealthy.

The UK’s poor social mobility ratings become more troubling when coupled with the present-day high levels of income and wealth inequality. The Gini coefficient, a meter of inequality within a distribution such as income or wealth, scales from 0 (perfect equality) to 1 (absolute inequality). It’s a favourite tool among economists and policymakers, helping to gauge the breadth of income or wealth disparities within or across nations, and guiding policies aimed at nurturing economic fairness and social harmony.

With a Gini coefficient of 0.34 before housing costs and 0.38, income inequality in the UK is quite high when juxtaposed against other developed European nations. Though it holds a slight edge over the United States, the UK’s skewed income distribution acts as a stubborn adhesive, keeping the socio-economic framework rigid and the dream of social mobility elusive for many.

Wealth inequality is a tale not just of income, but also properties, investments, and other assets, minus the liabilities. The Gini coefficient sketches an even more unequal narrative for wealth than for income. The richest 1% of households boast £3.6 million per household, a figure that skyrockets 230 times above than households at the opposite end of the spectrum.

Over the last thirty years, ONS data indicates a worrying trend in wealth inequality has emerged, undoing much of the progress made in the 20th century. In the early 1900s, wealth was extraordinarily concentrated, with the richest 10% controlling 92.7% of it, while the poorest half of the population shared a paltry 0.5%. By 1940, there had been a modest redistribution, with the top 10%'s share reducing to 83.8%, and the bottom 50%'s share increasing to 2.0%. This trend towards equality continued, and by 1970 the wealthiest 10% owned 64.5% of the wealth, while the bottom 50% saw their share grow to 5.0%. The most equitable distribution was recorded in 1990, with the top 10%'s share at its lowest, 46.0%, and the bottom 50%'s at its peak, 6.2%.

The reversal of wealth distribution trends in the UK after the 1990s is stark. By 2020, the wealthiest 10% saw their share inflate to 57.0%, a significant rise from the low of 46.0% in 1990. Conversely, the bottom 50% of the population saw their already small share of wealth diminish from 6.2% to 4.7%. These figures underline an escalating inequality, with wealth increasingly pooling at the top echelons of society, moving away from the egalitarian gains of the previous decades. It paints a picture where the socio-economic divide is widening, effectively deepening the chasm between the wealthy and the poor.

The muted reaction to three decades of widening wealth inequality in the UK might speak to a deep-seated mindset. Echoing Richard Rose's observation, societal equality isn't always pursued as a priority in England. This apathy may also stem from a Thatcherite belief in the natural order of meritocracy—where the wealthy are presumed to have earned their status. Furthermore, a cultural nostalgia for 'Britishness' could be at play, where the elevation of a privileged class is interwoven with national identity and heritage, perpetuating the status quo without significant public uproar. This complex tapestry of resignation, acceptance of natural social hierarchies, and reverence for traditional British norms continues to shape the collective consciousness around wealth and class.

Navigating the Labyrinth of British Aristocracy: A Legacy of Adaptation, Inclusion, and Resilience

Cecil Alexander's resonant hymn, "All Things Bright And Beautiful," with its striking verses, "The rich man in his castle, The poor man at his gate, God made them, high or lowly, And ordered their estate," encapsulates the enduring fabric of the British social hierarchy. This hymn, a staple of British upbringing across generations, succinctly articulates the class system's core belief: the divine and unchangeable nature of one's social position. Through Alexander's words, the immutable divide between privilege and penury is vividly drawn, portraying a society deeply segmented by birthright.

The British aristocracy, with its roots deeply embedded in feudal tradition, epitomises a centuries-old belief in the inherent superiority of certain lineages. This belief was institutionalised in medieval times, as monarchs rewarded their loyal nobility with lands and titles for military support, creating a rigid social hierarchy that has subtly morphed yet endured. The peerage system, featuring ranks from dukes to barons, solidified this stratification, ensuring the hereditary transmission of privilege.

Unlike the aristocratic upheavals that reshaped much of Europe, the UK's transformation has been uniquely gradual. The British aristocracy has witnessed a slow diminution of its overt political power, a process characterised by legislative reforms rather than outright abolition. This gradualist ethos reflects a broader British predilection for evolutionary change, revealing an astute adaptability among the elite. Concessions of power were strategically made when the threat of a complete overhaul loomed, allowing the aristocracy to exchange and translate their traditional forms of influence for modern equivalents of power, primarily land and wealth.

Crucially, the aristocracy's enduring influence has been bolstered by a willingness to absorb and integrate members from outside its traditional ranks, particularly the nouveau riche. This inclusivity has served as a strategic mechanism for defusing potential conflicts with rising powerful groups, ensuring the aristocracy's survival and the continued enhancement of its privileges. By opening its doors to those who have amassed wealth and influence through contemporary means, the aristocracy has reinforced its base, weaving new threads of wealth and power into its ancient tapestry, and thereby securing its place in the modern British socio-political landscape.

As of 2024, the ranks of the formal British aristocracy includes 805 hereditary peers, containing 30 dukes, 34 marquesses, 189 earls, 110 viscounts, and 442 barons. They are predominantly male due to the gendered traditions of succession. Notably, 92 of these peers retain legislative roles in the House of Lords, marking a significant deviation from the norm in European governance and underscoring the unique persistence of hereditary privilege in the UK.

This adept blending of old and new, of welcoming the economically powerful into the folds of traditional aristocracy, has not only preserved but also augmented the aristocracy's societal prominence. This strategic inclusivity and adaptability underscore a broader narrative of resilience among the UK's elite, enabling them to navigate the tumultuous currents of change while maintaining their storied legacy of privilege. Thus, the British aristocracy continues to evolve, melding historical lineage with modern capital, and in doing so, remains a powerful force within the fabric of British society.

Case Study: The Drax Family - Tradition, Transition, and the Tactics of Aristocratic Survival

The Drax family saga is a compelling illustration of how the British aristocracy has not only survived but thrived, navigating the waters of societal change while ensuring their privileged position remains unchallenged. At the heart of this narrative is Richard Grosvenor Plunkett-Ernle-Erle-Drax, a contemporary beacon of aristocratic continuity, whose life and career encapsulate the successful adaptation strategies of the UK's elite. His role as a Member of Parliament is built upon a foundation of historical privilege, wealth, and the invaluable networks fostered by an education at Harrow School, illustrating the pathways through which aristocratic influence persists in modern governance.

The political lineage of the Drax family further exemplifies the seamless melding of aristocratic heritage with contemporary political power. Richard Drax's ancestors, including figures like John Samuel Wanley Sawbridge Erle-Drax and the 17th Lord Dunsany, served as MPs for regions such as Dorset and Gloucestershire from the 1680s to the 1880s. The continuation of this tradition by Richard Drax, alongside a cousin who is the 19th and current Lord Dunsany, highlights a familial commitment to public service that doubles as a strategy for maintaining influence and relevance.

Central to understanding the Drax family's enduring influence is the Drax estate in Dorset. As one of the UK's largest private estates, held since the 17th century, it spans approximately 7,000 acres, including the village of Charborough. This vast landholding is more than just a symbol of wealth; it represents a continuity of power and presence in British society that few can claim. The estate underscores the family's ability to maintain significant socio-economic status through centuries of change, serving as a physical embodiment of their lasting legacy.

Apart from their significant land holdings, the Drax family's wealth was historically derived from sugar plantations in the Caribbean that used slave labour. The family's historical compensation following the abolition of slavery is particularly telling of the mechanisms that have protected aristocratic privilege through times of social reform. When slavery was abolished across the British Empire in 1833, the Drax family received what would be equivalent to over $3.5 million today for the freeing of 189 slaves. This compensation exemplifies how societal and legal reforms, even those aimed at correcting grave injustices, were structured in a manner that ensured the aristocracy's wealth and social standing were not just preserved but effectively endorsed.

The political lineage of the Drax family further exemplifies the seamless melding of aristocratic heritage with contemporary political power. Richard Drax's ancestors, including figures like John Samuel Wanley Sawbridge Erle-Drax and the 17th Lord Dunsany, served as MPs for regions such as Dorset and Gloucestershire from the 1680s to the 1880s. The continuation of this tradition by Richard Drax, alongside a cousin who is the 19th and current Lord Dunsany, highlights a familial commitment to public service that functions as a strategy for maintaining influence and relevance.

This case study of the Drax family brings to light the sophisticated strategies employed by the British aristocracy to adapt to the evolving landscape of society and governance. Their story is one of strategic adaptation, ensuring that changes—be they social, legal, or economic—do not destabilise their privileged position but rather are integrated in ways that consolidate their legacy. Through leveraging their historical assets, navigating the intricacies of modern politics, and benefiting from compensatory frameworks during periods of reform, the Drax family exemplifies the aristocratic art of survival and influence in a changing world. Their narrative is a testament to the ongoing interplay between tradition and adaptation within the British class system, where historical privilege continues to intersect with contemporary power structures.

The Three-Tiered Educational System: A Means of Preserving Privilege

Nelson Mandela once profoundly stated, "Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world," highlighting education's potential to be a force for societal transformation and unity. However, in the UK, this optimistic vision encounters a starkly contrasting reality. Professor Diane Reay of the London School of Economics notes that “Historically, the English educational system has educated the different social classes for different functions in society” and that “little has changed in relation to how the working classes are valued within education”. These observations underscore the UK's educational system's role in cementing elite networks and privileges, acting not as a lever for change but as a bulwark preserving the status quo and safeguarding the elite's power against any forces of change that might threaten their established positions. In modern Britain, one's status as an alumnus of an elite school often functions as the equivalent of an aristocratic title during medieval times, serving as a key marker of privilege and a gateway to positions of power and influence.

The UK's educational landscape is distinctly structured into three tiers: comprehensive schools, grammar schools, and public/independent schools. These tiers reflect broader social class divisions, serving as institutional embodiments of the upper, middle, and working classes within British society. State-funded comprehensive schools are open to all students but confront challenges like underfunding and overcrowding, which may lead to a relatively lower quality of education. State-funded grammar schools, while also publicly funded, are selective institutions offering higher educational quality and better resources, often requiring successful performance on the 11+ exam for admission. Fee-paying public/independent schools provide a rich educational experience, but access is typically restricted to the upper-middle and upper classes due to the substantial costs associated with attendance.

Historically reserved for aristocracy, public schools have evolved to accommodate the affluent, preparing students for leadership within and beyond the British Empire. The ethos of these institutions, encapsulated in the saying, "The Battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton," underscores their role in nurturing individuals for imperial governance and, post-empire, for domestic leadership.

The repercussions of this educational stratification are profound, extending into various sectors of British society. Data from the Sutton Trust and the Social Mobility Commission reveal a disproportionate representation of privately educated individuals within pivotal societal roles—politics, judiciary, media, and business—underscoring the symbiotic relationship between educational background and social mobility (or the lack thereof).

For example, the political and judiciary landscapes are strikingly homogeneous: 46% of MPs, 79% of the House of Lords, and 85% of senior judges hail from private or grammar schools. The media and business sectors exhibit similar patterns, with 68% of newspaper columnists and nearly half of BBC executives originating from these elite educational institutions. The prevalence of public school alumni in positions of power and influence is further underscored by the fact that 20 British Prime Ministers have been educated at Eton.

This educational elitism continues into higher education, with institutions like Oxford and Cambridge (Oxbridge) and the Russell Group universities maintaining a preference for students from public schools. Despite only 7% of UK students attending private schools, these students are significantly overrepresented at Oxbridge, being seven times more likely to gain admission compared to their peers from non-selective state schools. A staggering statistic from a 2013 London School of Economics study highlights the persistence of elite education across generations, with some families maintaining a presence at Oxbridge since the era of William II.

The influence of an Oxbridge education extends deep into the UK's power structures, with a significant portion of senior judges, MPs, Lords, Cabinet ministers, permanent secretaries, and diplomats boasting Oxbridge credentials—remarkable when considering that Oxbridge graduates comprise only 1% of the population. This educational system not only reflects but also perpetuates the UK's class system, with each tier acting as a cog in the machinery that maintains the status quo of privilege. The statistical evidence is a telling indicator of how deeply embedded these educational roots are in the fabric of British societal, political, and economic life, reinforcing barriers to social mobility and ensuring that the echelons of power remain accessible primarily to those from a privileged educational background.

Imagine if, in a similar vein to the current dominance of the privately educated within key societal roles, a comparable proportion of judges, journalists, cabinet ministers, and Lords were overwhelmingly black, Jewish, or Scottish. Such a scenario would likely provoke significant public outrage, spotlighting the stark inequalities and challenging the acceptance of such disproportionate representation. Yet, the ubiquity of the privately educated in these positions has been normalised to the extent that it often escapes critical scrutiny. This thought experiment underscores the peculiar acceptance of structural inequality when it's perpetuated by those from elite educational backgrounds, revealing a deep-seated familiarity that dulls the collective sense of injustice. It highlights how societal perceptions of fairness and representation are malleable, contingent on the groups involved, and underscores the urgency of addressing these entrenched disparities to foster a more inclusive and equitable society.

Aristocracy Reinvented: The Fisherian Elite

The data and anecdotes explored earlier in this chapter illustrate how nobility and their progeny continue to wield disproportionate influence in contemporary Britain. However, the last century has witnessed a subtle metamorphosis in the definition of 'elite', a transformation colourfully embodied in the life and philosophies of British polymath Ronald Fisher.

Fisher was born into the burgeoning middle class of London, on February 17, 1890, to George and Katie Fisher. His father carved out a successful career as an auctioneer and fine arts dealer, ensuring the family a comfortable position within the societal fabric of East Finchley, London. Despite this middle-class backdrop, Fisher's path to academic distinction was paved through merit, securing scholarships that led him from the prestigious halls of Harrow School to the esteemed corridors of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. Initially drawn to the abstract beauty of mathematics, Fisher's intellectual journey soon navigated towards the confluence of statistics and genetics, marking the genesis of a groundbreaking career. Many of Fisher’s methods are still used by modern researchers.

Fisher was a eugenicist and was deeply troubled by the observed inverse correlation between the fertility rates of what he termed the "most valuable classes" and those of the "lower classes." He posited 'value' in terms of intellectual capability and educational attainment, not wealth or lineage, advocating for policies that would encourage those he deemed genetically superior to procreate more prolifically. This, he argued, was crucial to prevent a dilution of desirable genetic attributes. Fisher's narrative, echoing through the corridors of modern conservatism, suggests an unyielding belief that the downfall of great civilizations—like those of the Egyptians and Babylonians—was rooted in the higher fecundity of the lower classes, overshadowing that of their 'superior' counterparts.

Fisher's discourse intriguingly detaches class from its traditional anchors of wealth and heredity, redefining it through the lens of intellectual achievement and education. Yet, he ventured further, inferring that intelligence was not just correlated with, but determined by genetic lineage, subtly implying wealth as a secondary characteristic, a mere byproduct of genetic fortune. The Fisherian ideal envisions a society where bastions of excellence like Harrow and Cambridge extend their embrace to the brightest minds from all societal strata, reminiscent of Fisher's own ascent. Nonetheless, this vision is veiled with an underlying assumption that superior genetic endowments are predominantly harboured within the existing elite. This insinuation overlooks the potential of middle and working-class prodigies, suggesting a misplaced belief that such individuals are exceptions rather than evidence of a widespread distribution of potential across all classes.

Fisherian views implicitly permeate British educational policy. Selective grammar schools and private school scholarships are heralded as vehicles of social mobility, ostensibly designed to pluck bright, underprivileged children from obscurity and place them within the echelons of the elite. This policy, however, masks a more insidious function: by sprinkling a handful of 'success stories' among the predominantly privileged student bodies, these institutions enhance their social acceptability and legitimacy, all the while maintaining their exclusive nature. The true function of these measures is not so much to dismantle barriers as to decorate them, creating the appearance of inclusivity and meritocracy.

Similarly, concerted efforts to funnel more working-class students into Oxbridge—whether through scholarships or the regular admissions process—echo this Fisherian ideology. The approach focuses on integrating a select few into the hallowed halls of these venerable institutions, rather than addressing the broader inequities that stratify British educational opportunities. This policy does not seek to redistribute the resources and privileges concentrated within Oxbridge to other schools; instead, it maintains a veneer of meritocratic selection, reinforcing the divide between the 'most valuable classes' and the 'lower classes.'

In the dialogue concerning genetic determinism's impact on British educational policies, the pronouncements and endeavours of notable establishment figures resonate, seeming to endorse Fisherian eugenic perspectives. Dominic Cummings, while advising Education Secretary Michael Gove, made a striking assertion: "a child's performance has more to do with genetic makeup than the standard of his or her education." Cummings proposes an educational paradigm that emphasises "drawing out" a child’s innate talents rather than simply imparting knowledge. He advocates for an elite education for the top 2% of individuals, based on IQ, similar to the education provided by prestigious schools like Eton. Pete Shanks, in his Huffington Post article, crystallizes Cummings’s viewpoint, summarising it as the "association of genes with intelligence, intelligence with worth, and worth with the right to rule," reflecting the persistent echo of Fisherian thought on genetics, value, and education.

Mary Wakefield, Spectator Editor and Cummings's spouse, engaged in a revealing interview with Robert Plomin, a controversial academic from King’s College London. Plomin's controversial beliefs include “Nice parents have nice children because they are all nice genetically” and “DNA isn’t all that matters, but it matters more than everything else put together.” Plomin argues that these 'facts' necessitate a profound reconsideration of “parenting, education and the events that shape our lives.”

In her reflection on the conversation, Wakefield includes Plomin's claim that “At one time people thought family members were similar because of the environment, but it turns out that the answer — in psychopathology or personality, and in cognition post-adolescence — the answer is that it’s all genetic!” Her narrative evolves from reported initial discomfort with genetic determinism to a recognition that “if IQ is measurable (it is) and highly heritable (that, too), then the diversity we see now in exam results isn’t going to melt away."

Mary Wakefield's professed unfamiliarity with the principles of genetic determinism is intriguing, especially in light of her marriage to Dominic Cummings, known for his views on the subject, but also given the well-publicised views of her father, Sir Edward Humphry Tyrrell Wakefield, Baronet and the proprietor of Chillingham Castle. In the year preceding the publication of Mary’s article, Sir Edward was captured on film in the evocative setting of his family’s crypt, a glass of wine in hand, delving into the topic of genetic determinism and its influence on life’s outcomes. He stated, “The quality is everything. In general, to be elitist, I think the quality climbs up the tree of life. And therefore, in general high things in the tree of life have quality, have skills, they get wonderful degrees at university, and if they marry each other that gets even better.” His commentary underscores an ethos of elitism grounded in the conviction of inherited superiority. This perspective was further highlighted in his reflections on social mobility and cross-class unions: “Intelligent and talented is lovely but I want parents and grandparents who’ve had hands-on success... Because one is the subject of one’s genes.”

Our examination of Fisherian elitism's lasting impact across sectors such as government, media, academia, and traditional aristocracy sheds light on its significant influence in shaping the dynamics of modern British society. The advocacy for an educational and social hierarchy rooted in genetic determinism by influential figures and their ideologies marks a contemporary reimagining of aristocracy. At its heart, British educational policy reveals a deep-seated belief in the inherent superiority of certain individuals and groups. By emphasizing individual advancement over systemic transformation, this policy subtly suggests that only a select few from lower social strata have the natural attributes required for success in elite institutions.

The facade of meritocracy subtly perpetuates the myth that excellence inevitably rises to the top, suggesting that the sustained dominance of the aristocracy and alumni of elite schools is solely due to their innate superiority and diligence. This perspective, seemingly embracing democratic ideals, masks the structural barriers and ingrained prejudices that hinder social mobility and fair access to opportunities, thereby normalizing and legitimising the existing social order.

However, this viewpoint neglects the collective advantages of a more egalitarian educational environment, one that doesn't reserve opportunities for excellence to a select few prestigious establishments but extends them throughout the educational system. The persistent resonance of Fisher's eugenic theories within British educational policy highlights an urgent need for introspection and overhaul. It advocates moving away from policies that superficially promote social mobility towards a significant reimagining of the educational framework. This shift involves moving from applauding the rare success stories of a few to uplifting many, breaking down the barriers that sustain inequality, and redefining what it means to be elite in a way that genuinely mirrors the varied talents and potential of all individuals.

Unveiling the Elite's Entrenched Networks: From Hiring Practices to Social Circles

In modern Britain the distinction of being an alumnus of a private school or an Oxbridge graduate serves as a powerful signifier of membership within the Fisherian elite. This elite status extends beyond mere social recognition, deeply influencing the dynamics within various professional sectors and reinforcing a societal structure that favours a select few. The pervasive influence of this elite group is maintained by several distinct yet interconnected practices, ranging from positive discrimination to an unchallenged presumption of competence, and a palpable disdain for those outside their exclusive circle.

The phenomenon of positive discrimination through affinity is vividly exemplified in the experiences and candid admissions of Sir Nicholas Coleridge. With a storied career spanning over three decades at Condé Nast and significant contributions to the arts and cultural sectors, Sir Nicholas has openly discussed his partiality towards fellow Etonians: “There are certain people who weren’t there, and I do admit that in some strange and awful way I think, Now, why weren’t they? and that it counts against them slightly. If we are being completely candid, I do accept that I prefer the company of Etonians to the company of people from any other school in the world.”

Sir Nicholas’ preference is not subtle; it's an explicit acknowledgment that an Eton background not only piques his interest but also negatively colours his perception of those lacking this prestigious educational pedigree. This bias is more than just a personal quirk; it mirrors a broader, systemic preference that can influence professional interactions and decisions within the circles of the elite, promoting a culture of exclusivity based on educational background.

Closely related to this affinity is the presumption of competence that automatically accompanies the elite's educational credentials. This presumption privileges the qualifications obtained from prestigious institutions over real-world skills or academic excellence demonstrated elsewhere. This bias permeates hiring practices, as highlighted by a study conducted by the graduate recruiter Milkround, which found that many employers filter graduate applicants based on their universities' league table standings. This approach not only limits the diversity of thought and talent in the professional realm but also reinforces the notion that only those groomed in the hallowed halls of elite schools possess the qualities necessary for success, while penalising those with good grades who chose local universities due to socio-economic factors.

Perhaps the most glaringly divisive aspect of the elite's influence is their disdain towards non-elite alumni and graduates, a sentiment that manifests both overtly and covertly in various social interactions and institutional cultures. The infamous Bullingdon Club at Oxford University, with its history of affluent exclusivity, notorious behaviour, and alumni like David Cameron and Boris Johnson, epitomizes this disdain.

A former scout for potential Bullingdon Club members during the mid-1980s recounted the outrageous conduct within the club, overlapping with the tenures of Boris Johnson and David Cameron. Her narratives include tales of hired female sex workers performing at lavish dinners, routine belittlement of women, intimidation of staff, and vandalism epitomised by rituals of room destruction upon someone's election to the club. The derogatory terms "plebs" and “grockles” used by Bullingdon Club members to refer to those from less prestigious educational backgrounds mirror the ingrained disdain towards individuals outside the aristocratic circle, further propagating the exclusivity of power corridors to a certain class. his contempt is not limited to raucous behaviour behind closed doors but seeps into professional environments, impacting hiring practices and workplace dynamics.

These manifestations — the affinity for fellow alumni of prestigious institutions, the unquestioned presumption of competence they carry, and the disdain directed at those from less privileged educational backgrounds — collectively underscore the entrenched networks of the Fisherian elite. This elite not only shapes the professional landscape but also perpetuates a cycle of preferential treatment, challenging the ideals of meritocracy and fairness.

Groupthink and the Elite

In the 1950s, psychologist Solomon Asch conducted a ground-breaking experiment to investigate the extent to which individuals conform to group consensus. Participants were asked to participate in a simple task: judging the length of lines. However, the twist was that all but one participant in the room were confederates of the experimenter, deliberately giving incorrect answers. The researchers were astonished by their findings. Even when the correct answer was obvious, many participants conformed to the group's incorrect judgment. This experiment illustrated the power of conformity and the willingness of individuals to suppress their own judgment to avoid standing out or going against the group.

As Asch’s experiments demonstrated, humans have a natural tendency to conform, but this tendency is at its most dangerous when groups are homogenous. Groupthink occurs when a group of individuals with similar backgrounds, perspectives, and shared values become insulated from external viewpoints and dissenting opinions, leading to flawed decision-making. Irving L. Janis, an American research psychologist, identified several antecedent conditions that may exist within an organisation or group, contributing to an environment conducive to groupthink. These conditions encompass structural faults in the in-group, such as homogeneity among group members in terms of social backgrounds and ideology, a high degree of insulation from external perspectives, a lack of impartial leadership, and a deficiency of norms requiring systematic decision-making procedures.

This concept finds a potent example within the British elite, where the affinity among alumni of prestigious institutions, coupled with an unquestioned presumption of competence and a palpable disdain for those from less privileged backgrounds, culminates in a fertile ground for groupthink. The graduates of fee-paying schools and Oxbridge, who have been raised within a culture designed to cultivate certain ‘right’ views and values, embody a homogeneity that significantly contributes to an environment conducive to groupthink.

When a group lacks diversity in terms of socioeconomic backgrounds, ethnicity, gender, and other factors, it can lead to a narrow range of viewpoints and ideas. The British elite often form tight-knit social circles and networks. This insularity can create echo chambers where group members primarily interact with one another and have limited exposure to external viewpoints. As a result, they may become less receptive to different ideas and perspectives.

The prevalence of groupthink among the British elite carries significant consequences for decision-making processes, particularly in the realms of governance and policy formulation. The uniformity in social, economic, ethnic, and gender backgrounds within this group results in a limited array of viewpoints, thereby diminishing the caliber of decisions made. A notable example, as highlighted in Chapter 1, is the misreading of the reactions of Northern Irish political parties during the Brexit negotiations, illustrating the detrimental effects of a homogenised perspective on accurate decision-making. Similarly, the pervasive narrative of the Union being "precious," which often dominates political discourse, can be linked to the overrepresentation of individuals from private school backgrounds within journalism and politics. This demographic is frequently exposed to and indoctrinated with British nationalistic rhetoric, while simultaneously being isolated from the diverse experiences and viewpoints of the working class, contributing to a skewed and uniform portrayal of national identity and priorities.

To counteract the pervasive influence of groupthink, it is imperative for British professions and institutions to actively seek and integrate diverse perspectives into their decision-making frameworks. Promoting open dialogue, valuing dissenting opinions, and fostering an environment where challenging prevailing views is encouraged can mitigate the risks associated with groupthink. Such efforts would not only enhance the robustness of decision-making processes but also ensure that the leadership and governance of the country more accurately reflect the broad spectrum of experiences and expertise present within society.

To dismantle the entrenched culture of groupthink that currently characterises the British national conversation, dominated by private school alumni and Oxbridge graduates, requires a concerted effort to challenge the deeply ingrained biases that underpin this phenomenon. The affinity decision-makers exhibit for fellow alumni of prestigious institutions, the automatic presumption of competence these educational backgrounds are believed to confer, and the palpable disdain directed at those from less privileged educational backgrounds—all contribute to a homogenised thinking process that is markedly vulnerable to groupthink. As long as the UK's leadership and influential positions remain predominantly occupied by individuals from a narrow, wealth-based educational background, the country's decision-making processes will remain highly susceptible to the pitfalls of groupthink, with its attendant risks of poor and uninformed decisions.

Case Study: Oxbridge and Public Schools: The Breeding Grounds of Chumocracy Amid COVID-19

Amid the tumult of the COVID-19 pandemic, a critical lens was cast upon the UK government's decision-making processes, revealing a deeply entrenched ‘chumocracy’ characterised by mutual backscratching, presumed competence, and a prioritisation of connections over merit. This network, primarily composed of individuals with aristocratic titles, elite educational backgrounds, and similar ideological leanings, played a pivotal role in shaping the response to the health crisis, often to the detriment of public trust and effective governance.

Critics argue that the UK government's reliance on emergency procurement regulations, which allow for the direct awarding of contracts without a formal tendering process in situations of "extreme urgency," was exploited beyond its intended purpose, sidelining established companies in favour of those with elite connections. This situation not only spotlighted the systemic issue of endemic cronyism within the government's contracting but also underscored the need for a return to open, competitive contracting as a default to ensure fairness, transparency, and value for money in public procurement

Baroness Dido Harding's appointment to lead NHS Test and Trace stands as a quintessential example of this phenomenon. Despite her limited experience in handling health crises, Harding's Oxford background and connections to senior Tories, including her spouse John Penrose, MP, raised eyebrows and questions about the meritocracy of her selection. Similarly, Dame Kate Bingham was appointed leader of the government's vaccine taskforce. Many felt that her public school and Oxford credentials and marriage to Tory MP Jesse Norman, underscored the perception that elite connections were significant factors in her appointment.

The controversy extended to government contracts, notably highlighted in the Public First case, where Rachel Wolf and James Frayne, both Oxbridge alumni with close ties to Michael Gove and Dominic Cummings, secured a significant COVID contract. This instance, alongside the revelation of an unlawful VIP lane for Personal Protection Equipment(PPE) procurement that favoured referrals from Tory politicians, underscored a bias toward elite networks. Michael Gove's referral of Meller Designs, owned by Conservative donor David Meller, into this VIP lane, resulting in contracts worth £164 million, exemplifies how financial contributions and ideological support could influence contract awards.

Further instances include Lord Agnew's referrals leading to substantial contracts and Lord Feldman's advisement that helped secure lucrative deals, illustrating the widespread nature of this chumocracy. Even more strikingly, Baroness Michelle Mone's referral of PPE Medpro, a company with direct ties to her and her husband, Douglas Barrowman, into lucrative government contracts worth £200 million, showcases the intersection of personal, professional, and party affiliations driving decisions during the pandemic.

It's troubling to observe that, during a critical time, Tory MPs and ministers seemingly prioritized their elite networks for lucrative PPE contracts, sidelining experienced domestic manufacturers who, lacking these privileged connections, were compelled to seek opportunities abroad, selling essential PPE to foreign governments instead of supporting their own nation's needs. This scenario underscores a disconcerting overlap between political influence and economic advantage, leaving capable, home-grown businesses out in the cold and NHS staff without the protection they needed.

The pervasive influence of this elite network — from public school and Oxbridge graduates to aristocrats with familial and professional ties — has highlighted a systemic flaw within British governance. The reliance on a narrow cadre of similarly educated and ideologically aligned individuals has not only fostered an environment susceptible to poor decision-making and profiteering but also undermined the principles of equity and transparency that should underpin public service.

This case study of the COVID-19 pandemic response highlights the critical need for diversifying the voices and perspectives within the halls of power. Challenging the status quo — the preferential treatment of fellow alumni of prestigious institutions, the unchallenged presumption of their competence, and the disdain directed at those from less privileged backgrounds — is imperative. As long as decision-making remains in the hands of a homogenous group selected more for their school ties than their aptitude or expertise, the UK will continue to be vulnerable to the pitfalls of groupthink, chumocracy, and ultimately, ineffective governance. This moment calls for a profound reassessment of how leaders are chosen and how policy is crafted, urging a shift toward a more inclusive, meritocratic, and transparent system that truly serves the public interest.

What Do Most British People Think About Class?

Exploring British society's views on class beyond the perspectives of the elite unveils a complex tapestry of attitudes, deeply entwined with perceptions of accents, attractiveness, and social standing. The Halo and Horns Effects provide a psychological framework for understanding these biases. The Halo Effect suggests that a positive impression in one area can positively influence perceptions in other areas, while the Horns Effect indicates that a negative trait can adversely affect perceptions of other unrelated traits. For instance, an attractive individual may be perceived as more intelligent or competent. Similarly, being overweight could result in being judged as stupid or lazy, regardless of a candidates actual qualifications.

The Halo and Horns Effects have their origins in the basic survival instincts of early humans, who relied on swift judgments with limited information to differentiate friends from foes. This capacity for rapid assessment, crucial for survival, has developed into the nuanced cognitive biases we recognize today as the Halo and Horns Effects. These biases influence our social interactions, decision-making, and evaluations across various contexts. Although these judgment mechanisms are rooted in human biology, they are significantly shaped by cultural contexts. The tendency to assign positive or negative values to certain traits may be universal, but the specific traits that receive positive or negative valuations are largely determined by cultural norms and values.

In the UK, the way individuals speak can significantly influence whether they are perceived positively or negatively, thanks to the Halo and Horns effects. Accents can either elevate one's social standing or subject them to prejudice, demonstrating the powerful impact of speech on personal and professional perceptions. Received Pronunciation, often linked to prestigious public schools and devoid of regional ties, emerges as a symbol of elitism. Historically cultivated within public schools to erase regional dialects, Received Pronunciation, also known as the 'Queen's English' or 'BBC English,' has become a marker of prestige, despite being used by less than 10% of the UK population, primarily those from public school backgrounds.

The influence of speaking with a Received Pronunciation accent on societal perceptions was examined in a study featured in the Journal of English Linguistics. This research utilized a controlled experimental setup where candidates participated in a simulated job interview, delivering identical responses but with varying accents—ranging from Received Pronunciation to minority, regional, or working-class accents. The findings were revealing: candidates speaking in Received Pronunciation were consistently preferred over their counterparts, despite having the same qualifications and providing identical answers. This preference was particularly strong when raters were over 45 years old and the counterpart spoke with an Estuary English or a Multicultural London accent. This experiment underscores the substantial weight of accent in societal judgments, suggesting that in the UK, an individual's accent can profoundly influence how their competence and professionalism are perceived, thereby reinforcing class distinctions in social interactions. Essentially, the accent associated with private schools triggers the Halo Effect, leading to more favourable assessments of the speaker's responses, while accents tied to minority or working-class backgrounds tend to invoke the Horns Effect, resulting in less favourable evaluations.

The Horns Effect is not just limited to perceptions based on accents but also significantly influences attitudes towards the socio-economic standing and the ability of different classes to afford various living expenses. A YouGov poll conducted in 2023 provides stark evidence of these attitudes, revealing a deeply entrenched belief system that ranks individuals morally based on their financial status, placing the poorest at the bottom and the richest at the top.

According to the poll, a notable portion of the British population harbours negative views towards those in lower economic brackets, particularly those on benefits. For example, 24% of respondents believe that individuals on benefits should not have access to basic utilities such as electricity, gas, or water. This negative sentiment extends to other essentials, with 26% opining that a balanced diet should be out of reach for benefit recipients, and 27% against the affordability of school uniforms for children in these families. The disapproval escalates for less essential needs, with 37% against haircuts and a significant 43% deeming internet access – essential for job searching and essential services – as a luxury unaffordable for those on benefits.

Moreover, approximately 8% of respondents feel that those earning minimum wage should also be denied these basic necessities, with a small fraction (1-2%) extending this harsh judgment even to individuals earning an average wage. This data points to a pervasive ideology that seeks to deny basic human rights and necessities to the lower classes, further amplified by stigmatizing labels such as ‘benefits claimant.’ Such labels seemingly trigger the Horns Effect, marking individuals as undeserving of fundamental rights and necessities.

The findings from the YouGov poll, coupled with insights into accent perception research, illuminate a troubling aspect of British societal dynamics: the internalisation of political and media portrayals that pitch non-elite groups against each other. These internalisations, even among those disadvantaged by such stereotypes (for example, those not speaking with Received Pronunciation), reveal a complex layer of class consciousness. By accepting and perpetuating negative stereotypes about their own economic or social groups, and positive stereotypes of elite groups, individuals may inadvertently reinforce the very class divides and prejudices that affect them.

This phenomenon suggests a deep-seated influence of media and political narratives in shaping perceptions and attitudes within and across social strata, leading to a scenario where the non-elite not only face discrimination from higher social echelons but also contribute to their own marginalisation through the unconscious internalisation of these divisive narratives. Such insights call for a critical examination of the role media plays in perpetuating class divides and the necessity for more inclusive and accurate representations that foster unity rather than division.

The Conservatives’ Reaction to Negative Social Mobility Statistics in the UK: A Shift Towards Individualism

Faced with concerning social mobility statistics, the Conservative Party in the UK adopted a significant ideological shift towards individualism. This strategy involved altering the leadership of the Social Mobility Commission, with Katharine Birbalsingh, a figure known for her conservative education views, at the helm. These views included that girls naturally dislike physics and that students use accusations of racism to bully teachers. Birbalsingh’s opposition to so-called “woke” culture and her support for promoting patriotism in schools would also have made her appealing to the Tory leadership.

Under Birbalsingh’s stewardship, the State of the Nation 2022 report exhibited a notable departure from its traditional focus on systemic barriers to mobility. Instead, it championed individual agency, hard work, and personal responsibility as the primary engines of upward social movement. This narrative adjustment seeks to broaden the Conservatives' appeal by redefining success and suggesting that success does not necessarily stem from competing against private school alumni or achieving white-collar status but through personal efforts within one's existing socio-economic milieu.

This narrative shift away from systemic factors to individual effort serves multiple objectives. It attempts to widen the Conservatives' electoral base, particularly among those who might feel alienated by the conventional aspirations of moving into white-collar roles or elite circles. Moreover, it subtly redirects the discourse on social mobility from climbing to traditional markers of success to recognising economic mobility across a broader spectrum of opportunities, including those in vocational and technical fields.

This reframing is politically astute, aligning with a populist appeal that downplays criticisms of entrenched elitism and systemic barriers, instead focusing on the supposed preferences of middle and working-class youth for remaining within their communities and excelling in their current professions. While the reframing is perfectly aligned with Fisherian elitism, it does not emphasise the belief system. Instead, it leans on a conservative belief in self-determination and individualism, steering public discourse away from structural critiques and towards a narrative that places the onus of mobility on the individual.

In essence, the Conservative reaction to negative social mobility figures does not aim to address or rectify the underlying issues of inequality or prejudice. Rather, it strategically shifts the conversation towards an ideological stance that justifies and maintains the status quo, reflecting a deliberate effort to reorient debates on social mobility to fit a conservative agenda.

How to Change

Although this book primarily focuses on identifying and critiquing the deep-seated ideologies in British society that lead to flawed policies, we briefly examine some potential solutions to the UK’s social mobility problems. The gravity of the situation demands it. The prevailing belief that the existing class structure is natural, and the acceptance of the notion that 'some people are better than others' as a cause of inequality, underscore a resistance to learning from countries with higher levels of social mobility and equality.

Looking to Finland, which has eliminated fee-paying schools and ensures equitable funding across all educational settings, might serve as a blueprint for the UK. Finland's educational approach prioritizes a cooperative, low-stress environment and offers a holistic education that moves away from sorting students via standardized tests. Its pillars—well-trained teachers, inclusive education, personalized learning plans, and additional support for students who need it—have propelled Finnish students to the top of global educational rankings. For the UK to cultivate a more equal society, emulating these educational strategies could be key. This would involve de-emphasising standardised tests, fostering environments that encourage teamwork and mutual learning, and guaranteeing that every school is equipped with comparable resources and access to skilled educators.

In higher education funding, the UK could learn from Germany and the Netherlands, which offer more equitable systems and wider access. Unlike the UK, where funding models heavily favors top research institutions like Oxford and Cambridge, Germany and the Netherlands ensure a more balanced distribution of funds across a variety of universities, including those focusing on vocational and applied studies. Both countries use inclusive funding formulas that support both teaching and research, promoting a diverse and innovative university landscape. This approach contrasts with the UK's reliance on student loans and a competitive funding model that benefits established universities.

Legal recognition of accent as a protected characteristic under anti-discrimination laws and measures to prevent discrimination based on university attended could address deep-rooted class biases in recruitment. Mandating equitable recruitment processes and transparency within organisations could also help address systemic biases.

Public awareness campaigns and community outreach programs could play vital roles in challenging classist attitudes and promoting inclusivity. These initiatives could educate the public about systemic barriers to social mobility and the value of a more inclusive society, fostering interactions and understanding across different social classes.

Implementing these policies may face resistance from the current government, which prioritises maintaining existing social hierarchies. However, such reforms are essential for dismantling entrenched class structures and building a more inclusive, diverse, and egalitarian society.

Conclusion

We began this chapter with Richard Rose’s that the quest for social equality, while universally unattained, is notably underappreciated as a worthy aspiration in the UK. The tapestry we've since unraveled—spanning the stark realities of inequality, the stubborn grip of aristocracy, the cultivation of a Fisherian elite, the exclusivity enshrined within private education, the educational system's role in perpetuating class divisions, the adverse impacts of groupthink and cronyism, and the Conservative efforts to cast inequality in a less negative light—illuminates a landscape where the valuation of equality is not merely overlooked but actively subdued.

This exploration brings into sharp relief the complex and often indifferent stance towards equality that permeates British society, revealing an entrenched hesitance to pursue a genuinely egalitarian community. Far from being a benign oversight, this attitude represents a calculated cultivation of neglect.

Our journey through both statistics and narratives uncovers that the barriers to a more equal society are not mere relics of bygone eras but are upheld by prevailing attitudes that resist social mobility and diminish efforts to bridge class divides. These societal attitudes are not fading remnants but are actively crafted and perpetuated, forming formidable obstacles to equitable progress.

Understanding the historical and present-day context of these attitudes is crucial. It lays the groundwork for a comprehensive reform aimed at uprooting the deeply entrenched social hierarchies that privilege some over others. Embarking on such a reform is imperative for reshaping the debate on social mobility and class in the UK, with the goal of forging a future marked by greater equality and social unity.

Achieving true equality in the UK transcends mere policy and legislative reform; it calls for a profound transformation in Britain’s collective mindset and societal norms. he initial step is a frank acknowledgment of the depth of existing inequalities and the mechanisms that perpetuate them. The second step is to understand one’s own internalisation of powerful, prejudicial attitudes about the ‘lower’ classes. Advancing towards the ideals of equality requires relentless determination to confront and dismantle deep-seated beliefs in fixed social hierarchies. As Britain faces these persistent challenges, the pursuit of equality stands as urgent and vital, highlighting the continuous imperative to reassess and reform societal attitudes for a future shaped by inclusivity and fairness.